[translations idioma=»ES» url=»http://rgnn.org/2014/01/09/crisis-politica-en-tailandia-suma-y-sigue»]

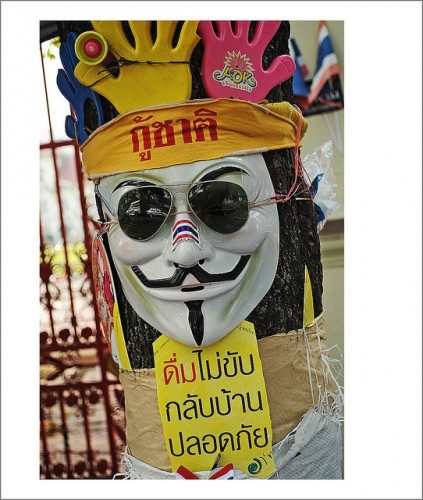

THAILAND. On February 2nd, 2014, Thailand will be holding legislative elections. Elections, called upon to put an end to a tumultous period of governance led by current Prime Minister Yingluck Shinawatra (2011-2013), the sister of the country’s previously overthrown leader Thaksin Shinawatra. Yingluck Shinawatra has seen how the opposition, by means of street protests and the withdrawal of their representatives from parliament, has rode the current legislation into the ground, and brought an end to it. The government thus contemplated holding elections as the sole way out of a profound political crisis, which has been devastating Thailand since 2006, and which has entered a new phrase in these past months.

The opposition, centered on the Democratic party and the People’s Democratic Reform Committee (PDRC), has announced that it will boycott the elections, a phenomenon closely linked to the 2006 elections, in which Thaksin Shinawatra’s party competed against an opposition that didn’t actually run for election, deeming them fraudulent. Months after, Thaksin Shinawatra’s government was overthrown by a coup d’état, led by the military and supported by the Royal House of Thailand.

Will 2014 follow in the footsteps of what happened in 2006?

The answer is unsure, but it is possible to argue in favor of three important reasons for which the upcoming elections will not succeed in bringing an end to the political instability that Thailand has been suffering since the military coup of 2006, and which ended Thaksin Shinawatra’s cycle of power (2001-2006).

First, the fact that the opposition is not going attend the elections distorts any outcome and government that emerges as a result of the process. The decision of the opposition undermines and discredits the entire electoral scheme, including Thailand’s political parties. As such, the first of Thailand’s three great crises: the crisis of the country’s very democratic political system. In fact, the nation’s last five electoral processes celebrated have been comfortably won by parties connected to the Shinawatra family. So, too, will the next electoral process follow in the same footsteps, without stabilizing the country.

Secondly, neither the military nor the monarchy appear to be possible sources for reaching consensus. The participation of both in the 2006 military coup implies that a great number of Thais don’t view their political reappearance as possible arbitrators in light of the reigning political blockade.

Thirdly, since the beginning of 2004, the south of Thailand has been witnessing rebellions, protagonized by the muslim part of the community. Since then, and in accordance with the statistics published by the Internal Security Operations Command, 5,296 people have died, and 10,593 have been injured as a result of more than 15.192 acts of violance committed in the south of the country. Rebellions that have been intensifying year by year, in light of the paralysis of the central government. These rebellions are not only the main focus point for insecurity in the zone in question, but also in Southeast Asia as a whole.

Thailand suffers three great, interconnected crises, the overcoming of which necessitates a grand political agreement that melts down the country’s current drained political framework. This will determine the direction that Thailand, one of the leading country’s of the region will take; a country that, throughout history, has known to maintain independence, and to this date, has known succeed in resolving its imminent issues.