Still life paintings have been occupying the lowest position in the hierarchy of genre, art theorist Samuel van Hoogstraten called them “foot soldiers in the army of art.” Though still life objects have been depicted since ancient Greek and Roman time, for centuries, they served only as a backdrop for the mythological, religious or historical drama taking place in the front stage.

Nonetheless, still life paintings managed to climb up the ladder in the 17th century in a piece of land that thrived on maritime trade, the Netherlands. Just like all other Dutch Golden Age paintings, Stillevens were known for their close resemblance to reality, paintings that fool the eyes. Given the objects’ inanimate nature, many praised this genre for its meditative power, especially when the interpretation of still life paintings have been focusing on the objects’ symbolic meanings. However, what is equally, if not more, informative and characteristic of still life paintings is the seemingly chaotic arrangement of the objects.

1. Art Period

An early painting by Pieter Claesz provides a great example:

Pieter Claesz, Vanitas with Violin and Glass Ball, c. 1628, oil on panel, 36cm x 59cm, Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Nuremberg, Germany | Wikimedia Commons

This piece shows a few dominant characters of Dutch still life paintings: diagonal composition, asymmetry, interplay between light and shadow, meticulously realistic depiction of still life objects. These reflect the exuberance and dynamism of the Dutch Golden Age, as well as the Baroque style that swept through Europe and wrapped the continent in gold and ornamentation in the 17th century.

Baroque was an art style that erected out of movement and unrest in Italy, as a successor to Renaissance and Mannerism, it was a combination of the rational and irrational, the restricted and rule-breaker. Baroque paintings were characterized by the theatricality, dynamism and sensual appearance. Italian Baroque influenced Dutch Baroque in the use of tenebrism (extreme light-and-shadow contrast):

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, The Calling of St Matthew, 1599-1600, Oil on canvas, 322cm x 340cm, San Luigi dei Francesi, Rome, Italy | Wikimedia Commons

Despite the stylistic similarity, one important distinction between Italian and Dutch Baroque was that little religious paintings were created in the Netherlands during the Baroque era, this was largely due to Dutch Protestant culture. Largely amount of Christian paintings and decorations in churches were also destroyed due to Iconoclasm in the 16th century.

2. Historical Background

The 17th century Netherlands welcomed various changes. Politically, it declared of independence from Spanish Habsburg in 1648. Economically, it was made prosperous by trade in the 17th century, the geographical location of the Lower Countries made the development of sea navigation and ship-making an obvious consequence. Socially, it was a peaceful time with little war or conflict. In terms of religion, the Netherlands was a Protestant country influenced by Calvinism, Dutch generally had high religious tolerance, and only around one-third of Dutch population were Catholics.

Intellectually, Dutch were still relentless in extracting the essence of everyday life and make lessons out of it. Artist Pieter Brueghel the Elder put them together in the Netherlandish Proverbs to present Dutch wisdom.

Pieter Brueghel the Elder, Netherlandish Proverbs, 1559, Oil on oak wood, 117cm x 163cm, Gemäldegalerie, Berlin, Germany | Wikimedia Commons

Interestingly, the Dutch art market was very much secularized in the 1600s, and it functioned just like today’s! Galleries were printing catalogues to attract viewers and art buyers, art dealers commissioning paintings to gain huge profit, even artists were rapid in responding to consumer demand. It was estimated that there were around 5-10 million paintings were produced by different artists, but unfortunately only a less than 1% survived.

3. Sub-genres

Many themes of the still life paintings were related to wealth and its consequences, they can be categorized into 5 sub-genres.

Vanitas Paintings

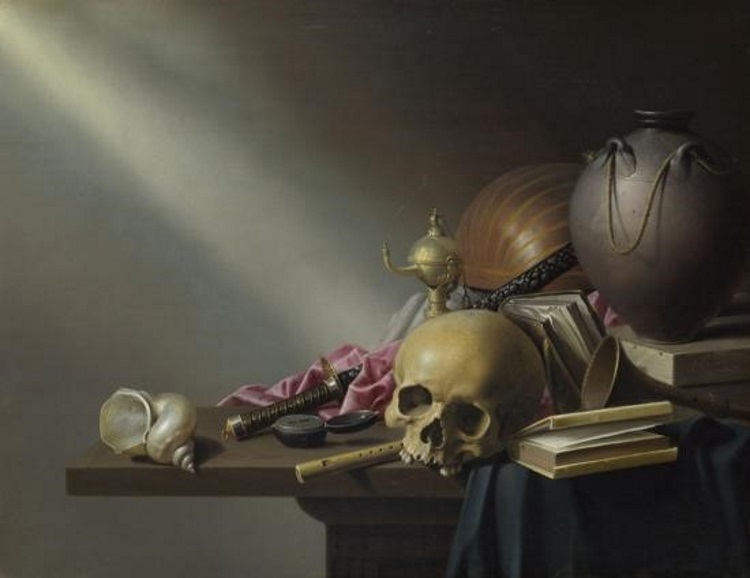

Harmen Steenwyck, Still Life: An Allegory of the Vanities of Human Life, c. 1640, Oil on oak, 39.2cm x 50.7cm | The National Gallery, London, U.K.

This sub-genre displays the vanity and emptiness of life. The chaotic arrangement of objects suggests that presence of someone before this scene was depicted, but gone. The grievance of life and death is made even more remarkable by the monochrome palette. The message is clear: despite the knowledge and wealth one might possess in this life, nothing can be carried away when death comes.

Breakfast and Banquet Paintings

Floris Claesz. van Dijck, Still Life with Cheese, c. 1615, Oil on panel, 82.2cm x 111.2cm | Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, Netherlands

The abundance of food and a wide variety of food choice have always been important indicators of high living standard. In food paintings, dairy products were often depicted, which bring out a famous Dutch proverb: “Dairy on top of dairy is the work of devil.” The same messy setting is also observed here as in vanitas paintings.

Ostentatious Paintings (Pronkstilleven)

Willem Kalf, Still Life With a Nautilus Cup, c. 1662, Oil on canvas, 79.4cm x 67.3cm | Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid, Spain

This type of painting has close relationship with the affluent life brought by sea trade and was usually commissioned by wealthy merchants who brought back exotic goods from the Far East and Central Asia. The commissioner wished to display their possessions through the paintings, as well as their aspiration for life.

Flower Paintings

Jan Davidsz de Heem, Still Life with Flowers in a Glass Vase, 1650-1683, Oil on copper, 54.5cm x 36.5cm | Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, Netherlands

Flower paintings display yet another ancient Dutch wisdom on art: “Ars longa, vita brevis” (Art is long, life is short). They are certainly a pleasure to see during a cold winter in the Netherlands, for permanence of artwork outlasts the transient beauty of flowers themselves. But isn’t this another mockery at humans’ will to conquer nature?

Game Pictures

Jan Weenix, Still-life of Game, 1706, Oil on canvas, 123cm x 100cm, Private Collection | Wikimedia Commons

Hunting was a royal activity that only aristocrats had the time and resource to perform. While it was no doubt another sub-genre that displays one’s wealth and social status, a sense of melancholy often accompanies these paintings. Especially the way in which the dead animals’ bodies are twisted and distorted.

4. Symbolic Meanings

After considering the composition and its relation to the art period and historical context of still life paintings, these symbolic meanings should make much more sense to us.

Life and death: skull, oil jar, pair of birds (resurrection of the soul after death)

Knowledge: books, musical instruments

The passage of time: chronometer watch, hourglass, burning candle

Transient beauty: flower, dead animals, bubbles

Dynamism of life: insects, butterfly

Two different world-views (truth and vanity): reflections on glassware or shiny objects, mirrors

Wealth and earthly possessions: nautilus cup, rugs, Chinese porcelain, food/ banquet

But above all, there is one important hidden meaning that modern viewers have always overlooked. The still life painting itself was a confident show-off of the painters’ own artistic ability to specialize in one genre and reproduce reality.

David Bailly, Self-Portrait with Vanitas Symbols, 1651, Oil on wood, 65cm x 97.5cm, Stedelikj Museum De Lakenhal, Leiden, Netherlands |Wikimedia Commons