It can never be like at home abroad. The food you eat, the drinks you gulp, and the shops you go to, although they can be branded to be from your country, are an inch away from your taste or expectations, even at their best. It could be an extra spoon of salt, a little less strong of a smell, or price that is hard to believe for your beloved product. Maybe the fact that you are somewhere else, not at home, makes traces from home at abroad to always be approximations of your standards.

When I first came to Madrid to spend two weeks here, I was first tempted to find footprints of people and culture from Korea, just as other tourists or residents from my country would possibly do. But soon, the scope of my interests became broader to include those of Chinese, after seeing so many East Asian neighbors on the streets of Madrid, with a concentration that I found to be unexpected in Spain. Moreover, considering the proximity of two countries, along with many similarities and nuanced differences between two cultures, I wanted to discover how their traces have been remained. Walking from Plaza de Espana to unpopulated streets surrounding Opera, I was able to know how restaurants and shops by Chinese and Korean owners have contextualized themselves in Madrid. The specificities of each cultures seem to have been maintained according to the philosophy of the owners but have also been modified to local situations, thereby creating a remix of different cultural flavors.

Little China beneath Plaza de Espana

Entrance to ‘Yu Long’ and ‘China’ from Plaza de Espana | Mingu Cho

The first time I heard from people on Calle Gran Via that ‘Yu Long’ is inside the parking lot of Plaza de Espana, I thought they must have meant that the restaurant is on the basement of ‘Barcelo Torre de Madrid,’ a hotel next to the square. Having failed to find anything below the ground floor of the building, I got out of it and walked straight into the parking lot in front of the hotel. After diverting away from the cars that come and go, I found a small entrance in orange on the first basement that led to the Chinese restaurant. Inside ‘Yu Long’ was bustling with an even mix of Chinese and Madrilenos, who were having traditional Chinese food, from baozi (dumpling) to zongzi (rice dumpling wrapped in bamboo leaves) and jiandui (fried round cake stuffed with red bean), which the latter is typically consumed during Dragon Boat Festival in the mainland.

One of the customers inside was Tony, the owner of Chinese supermarket, which succinctly introduces itself by the name of ‘China.’

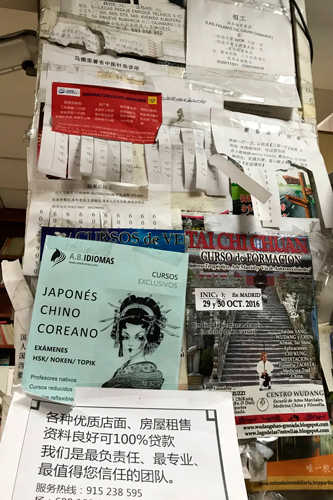

Paper advertisements in Chinese and Spanish in ‘China,’ including one that offers courses for East Asian languages | Mingu Cho

Although ‘China’ is unlike Madrid’s typical supermarkets that are on the open streets and have signs that say alimentacion (supermarkets), I hoped Tony could answer why a great majority of supermarkets in the city is owned by Chinese people. The laoban (boss in Chinese) explained that a lot of people began to come to Madrid from 1980s, a period when international migration from China gained a new momentum. According to Tony, it is “easier for Chinese to open a supermarket” because people have formed “a line of business.” Considering how difficult it is for immigrants to venture financially into a new environment and the fact that corner stores are always needed in a neighborhood for locals as well, Chinese people have made use of the demand from both sides to create a business infrastructure. Not only did Tony refer to the solidarities of Chinese in Madrid, but he also mentioned the diversity of jobs that they have, pointing out that “Chinese can be artists, doctors, journalists, and more.” His clarification diffused the stereotype that ‘particular’ people do or should take a ‘particular’ job, testifying that the lives and culture that surround ‘China’ are not as simple as its name.

A Peek Into the Lives and Thoughts of Chinese Immigrants at Calle de Leganitos

Supermarket with signs of Korean food and products, including Korean beer advertisement at its entrance | Mingu Cho

After finishing conversation with Tony, I crossed the same sidewalk and arrived at the entrance of Calle de Leganitos, a street where different Chinese restaurants and shops were waiting for me. At first, the street did not look like where a lot of Chinese shops and diners are located because it does not have gigantic signs or billboards in their language, just as China towns around the world do. However, past ‘Cerveceria Royal’ and straight on to the calle (road) are ‘Hong Kong Kitchen and Tea Restaurant’ and ‘Restaurant Pho 26,’ which signals that the visitors’ East Asian experience has officially begun. Having passed the peluqueria (barbershop), massage shop, and another Chinese supermarket, I arrived at a bookstore called ‘Libreria Liang You,’ a shop with its sign engraved in blue Chinese character.

It was Mr. Zimfu, the owner who has lived in Madrid for 18 years, who enabled me to get a glimpse of the generational gap among the Chinese immigrants in the city. When few of the Madrilenas in the store left after buying some stationeries, he told me that “there are not much tourists who come to ‘Calle de Leganitos,’” as if he has wished for their existence. Even when he was asked if there is a flow of Chinese customers or students, Mr. Zimfu answered that not many people study with book nowadays but rather with their laptops and at cafés, which is why he expanded his shop’s services to “photocopying, printing, and selling phone cards.” While the alterations in Mr. Zimfu’s business are observable across generations in other cultures or countries, the magnitude of his experience seems to have been amplified from the fact that he is working in a foreign country as an immigrant.

Mr. Zimfu’s ‘Libreria Liang You’ from outside | Mingu Cho

The Encyclopedia of Mr. Jefon and Google

A little above from the bookstore was ‘Tiendas de Yoye,’ a gadget and electronic components shop where a lot of locals come to buy cables and cell phone cases. Mr. Jefon, the owner, moved to Madrid twenty years ago from Zhejiang province in China to find a work. When I asked him casually when did Chinese people first come to Spain, he went into a Spanish Archive in Chinese via Google, found that they first arrived in 1577 and changed his finding into Korean on Google Translator. Not only that, Mr. Jefon also found an article written in 2014 on Financial Times and showed me that there are “180,000 Chinese nationals living in Spain,” this time typing the number of people on his electronic calculator.

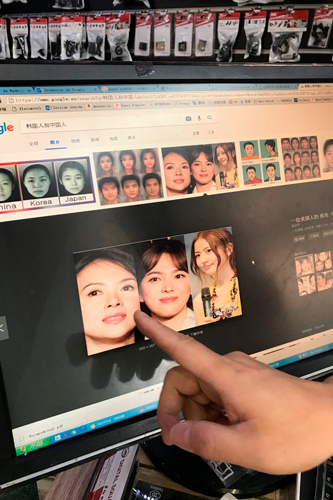

Mr. Jefon’s Google Search of comparing the faces of East Asian celebrities | Mingu Cho

Astonished by his eagerness to talk, I further asked him if Madrilenos can tell apart Chinese and Koreans, a question I have had since Day 1 in Madrid because a lot of locals had mistaken me for Chinese. Although confusing the nationality of a person occurs elsewhere too, I wanted to get his perspective on how the locals’ confusion would work in a country where their familiarity to East Asian culture or people could be expected, considering the large number of immigrants. “Chinese, Japanese, and Koreans are the same,” he said. Mr. Jefon spoke in his broken English that “only language is different” among people from the three countries. When questioned if he considers differences among the cultures of each country, he replied in Chinese, “They are the same. People with yellow faces are the same. We look the same.” While I was trying to reply to him, he interrupted by showing a photo from Google of Chinese, Japanese, and Korean female celebrities juxtaposed together. “Just as Spanish people can confuse us to be from the same country, we can likewise find it difficult to distinguish Spanish person from a Portuguese,” the boss explained.

Madrilenos passing by ‘Tiendas de Yoye’ | Mingu Cho

His focus on the similarities seem to imply a cheerful note of how people from three countries could collaborate with each other, particularly when it comes to living abroad. Still, his adamant belief in the unanimity of East Asian people seem to have undermined how the specificities of each culture must be respected. Wondering if there are any places in Madrid that can show the distinctions between Chinese and Korean culture, I first began to search for Korean restaurants nearby, which I found one at the top of Calle de Leganitos on the Google Maps.

Korean Restaurants in Madrid: Originality of Food vs. Reality of Localizing Them

‘Arirang’ from outside | Mingu Cho

On the right at the top of Calle de Leganitos is a restaurant called ‘Arirang,’ which means Korean folk song, also considered as the country’s national anthem. Upon arriving at the entrance, I hesitated to enter because the dark red exterior of the restaurant and the sign inscribed in Chinese, English, and Korean in gold color had more ambience[1] of Chinese restaurant than Korean one. Inside, the owner and waitresses were all Chinese, so were the customers. The menus were both in Chinese and Korean, which meant that customers from both countries come to the restaurant. Coming out from ‘Arirang,’ it took me about five minutes to reach Opera station. From the adjacent Plaza de Isabel III, it took me three minutes to find another Korean restaurant called ‘Sarang Bang,’ which means ‘room for customers’ in Korean. The restaurant was empty except for the Korean owner, one Spanish waiter, and one Bangladeshi chef, an ethnic mix disparate from all-Chinese demographics at ‘Arirang.’

After another three-minute walk, I arrived at ‘Restaurante DaDam[2],’ which had a door that resembles the one for Hanok, Korea’s traditional house. Unlike the two Korean restaurants I had visited, DaDam had owner, cook, and waitress who are all from Korea. The owner, Ms. Yoo Jae In, who first came to Las Palmas in Spain 18 years ago, opened the restaurant in 2013 and has ever since made its cuisines alongside the chefs. “Most Korean restaurants in Madrid have Korean owners but their kitchens are operated by non-Koreans,” said Ms. Yoo. Responding to the query of whether the food is catered to the taste of Koreans or Spanish people, Ms. Yoo reminded that “they are served just as they are because the original taste is important when trying to promote Korean food abroad,’ a reason why she buys the ingredients from Korean supermarkets in Madrid and imports them from Korea. Before I left, Ms. Yoo drew my attention to the Taeguk mark on the logo of the restaurant, a symbol meaning ‘supreme ultimate’ created in the 5th or 6th century, before it came to be used for Taegukgi (South Korea’s national flag) in the 20th century. Despite her identifying the food with the country’s ancestry, she also expressed the difficulty of maintaining the authentic taste in the cuisines because “there are not many Korean people” and chefs, especially in Madrid.

Taeguk mark on the sign of ‘Gayagum Restaurant’ | Mingu Cho

Back to Opera station and this time to Calle de Bordadores, I reached ‘Gayagum Restaurant,’ which had Taeguk mark on its sign, too. Just as the restaurant’s name, which means Korea’s traditional string instrument, the interior was decorated with various hints of Korean art, ranging from hahoetal (traditional mask worn in ceremony and satirical play) to traditional calligraphy. At its fifth year, the canteen is managed by workers from Bangladesh, Spain, and Philippines, and owned by Korean couple, who grows the vegetables for ingredients at their private farm called ‘Eres Corea[3] (You are Korea).’

Korean traditional masks decorated on the wall of ‘Gayagum’ | Mingu Cho

As for the absence of Korean chefs in Madrid’s Korean restaurants, Alex, a 48 years old Filipino-Spanish waiter at ‘Gayagum’ who moved to the city twenty years ago, expressed that he “[cannot imagine] South Koreans living in Madrid who would be willing to work as a waiter or as a chef,” both because of the small number of Korean people in Madrid and an engraved structure of their restaurants where “only the owners are from the country.” This was in clear contrast to the Chinese line of business, restaurants and supermarkets included, where owners and workers are all from the same place, as previously explained by Tony from ‘China.’ With regards to Korean restaurants like ‘Arirang’ that are managed by non-Koreans in all different aspects, Alex defined “Korean cuisine [as] fad cuisine these days,” a transformation that I believe brings the question of how to maintain the authenticity of food and adapt it to local situations.

Conclusion

While the ethnic identity was greatly emphasized in Chinese supermarkets and restaurants, mainly due to the size of their community and solidarity among the people, the small number of Koreans in Madrid and the lack of support system amongst them have made it more difficult for them to maintain their cultural origins and make them known to the public, particularly when it comes to food. For the latter, the localization of culture has not yet occurred extensively as much as the localization of business. Furthermore, the distinctions between two cultures seem to have sometimes blurred out in a foreign place, with a majority of Chinese supermarkets selling Korean products and Chinese owners selling Korean food.

Looking at how the restaurants and shops adapt to Madrid was also a process of discovering how I adapt in a different country, including how I am shown to others, how I change according to their expectations, and how I maintain my identities. Take a walk from Plaza de Espana to Opera and discover the shops where a remix of different cultures occur, the stories behind how they have come to place, and also yourself. After all, it’s not so long of a walk.

Fact Box:

Yu Long

Plaza de España, s/n, 28008 Madrid

Call: 915 48 21 03

Opened every day from 10AM to 1AM

Libreria Liang You

Calle de Leganitos, 22, 28013 Madrid

Call: 915 59 03 69

Opened every day from 10AM to 9PM

Tiendas de Yoye

Calle de Leganitos 1 Local 28013 Madrid

Call: 915 418 473

Arirang

Calle de la Bola, 12, 28013 Madrid

Call: 910 29 82 60

Opened every day except for Wednesday from 12:30 to 4:30 PM and from 8 PM to 12AM

Sarang Bang

Calle de la Amnistia, 5, 28013 Madrid

Call: 914 04 10 54

Opened every day except for Monday from 1 to 4 PM and from 8 to 11PM

Restaurante Dadam

Calle Factor, 8, 28013 Madrid

Call: 911 29 85 84

Opened every day except Sunday and Monday from 1 to 4:30 PM and from 8 to 11:30 PM

Gayagum Restaurant

Calle de Bordadores, 7, 28013 Madrid

Call: 915 42 04 88

Opened every day from 12PM to 12AM

[1] Red and gold are juxtaposed together in Chinese culture, for the red “symbolizes good fortune and happiness” and gold “symbolizes good luck.” (http://www.thedailychina.org/what-is-the-significance-of-red-and-gold-in-chinese-culture/)

[2] Make sure to search ‘Restaurante Dadam’ on Calle Factor. ‘Dadam Restaurant,’ which is on Calle San Antonio, is an hour away on foot, although it’s managed by the same owner.

[3] In front of the restaurant is an exhibit of the restaurant’s cuisines, wrapped in plastic vinyl, and a sign that reads ‘llenamos las mesas con ingredients organicos que cultivamos a mano,’ which means that the owners farm organically by themselves to prepare the food.