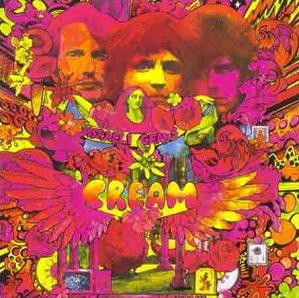

AUSTRALIA. Over the last 50 years most have come to know the bright, surreal images of the psychedelic counter culture movement that sent shock waves through the 1960s. The often drug-induced music and art movement sought to challenge typical perceptions and evoke enlightenment. What many don’t know, however, is that the swirling colors that adorn famous 60s-era album covers, such as those of Bob Dylan, Jimi Hendrix and Cream, were the brainchild of Martin Sharp; Australia’s foremost Pop and psychedelic artist.

The legendary Sydney native passed away on December 1st, 2013, at the age of 71, but his creative legacy will live on for years. Although he was considered a Pop Artist, Sharp had a distinct style that set him apart from the rest of his contemporaries. His mark on the era included mystical music posters and band art work, characterized by the bright colors, repetitive patterns and three-dimensional fonts.

Music inspired much of Sharp’s work — he was a big fan of Bob Dylan. He aimed to display the feeling of the music, an example is his 1971 poster of Jimi Hendrix, for which he used a Jackson Pollock-inspired background to symbolize the famed guitarist’s style.

Sharp claimed that the psychedelic lifestyle changed his view of the world around him, allowing him to see everything in a more positive light.

“There was a feeling of optimism, the possibility of the world working. That was definitely part of the experience,” he said.

He co-founded Oz magazine in 1963, with his partners Richard Neville and Richard Walsh. They became known as the “Oz Three”, and the magazine’s objective was to spread artistic and political freedom. They became the subjects of controversy several times for publishing “offensive” material, including a photograph of Sharp and two friends pretending to urinate into a sculptural wall fountain. This famous image was responsible for landing the Oz Three in jail in 1964, however supporters caused an uproar leading to their acquittal two years later.

The jail time turned out to be a blessing in disguise. Realizing that they had no future in Australia, where they would face countless opposition, Sharp and Neville moved to London where they established the London Oz.

In London Sharp immersed himself in the alternative art and music scene thriving in the city. It was around this time he met young Eric Clapton, the lead singer and guitarist of Cream. As a result, Sharp was commissioned to design the famous psychedelic collage for Cream’s 1967 album Disraeli Gears.

He moved back to Australia in the 70s, and dedicated his later life to keeping Sydney’s Luna Park open to the public. In 1979, a devastating fire in the park killed one adult and six children. Sharp blames the fire for his spiritual reawakening, after rejecting religion in his teens.

“God spoke through the fire in a mysterious way,” he later told ABC’s Anna Marie Nicholson. His three paintings Pentecost, Golgotha, and Eternity honor of the tragedy.

Following his return to Sydney also opened the Yellow House Artist Collective, a center for living and pop art. The house was a canvas and performance space with a membership including innovative Australian artists such as George Gittoes and Ellis D Fogg.

In his later years, Sharp kept a lower profile, becoming somewhat of a recluse, but never losing his connections or circle of friends in the art world. Sharp passed away in his home after battling a chronic lung disease, inciting widespread mourning for the man who symbolized the sixties.