The Xingu river flows north 2,271 kilometers from the central savanna region of Mato Grosso to the Amazon River; its basin is an emblem of Brazil’s cultural and biological diversity, being home to 25,000 indigenous people from 40 ethnic groups.

The Belo Monte Dam complex, projected to be the third largest in the world, is designed to divert 80% of the Xingu River’s flow, which will thus devastate an area of over 1,500 square kilometers of Brazilian rainforest.

The dam complex is still under construction. It is part of a wider plan of several new hydroelectric dams, to be constructed all around Brazil to guarantee national energy security. A plot hatched not in recent times, but since 40 years ago, during the Brazilian military dictatorship.

The roots of greed in Brazil

Plans for what would later be called the Belo Monte Dam complex began in 1975 during Brazil’s military dictatorship, when Eletronorte contracted the Consórcio Nacional de Engenheiros Consultores (CNEC) to realize a hydrographic study to locate potential sites for a hydroelectric project on the Xingu River. CNEC completed its study in 1979 and identified the possibility of constructing five dams on the Xingu River.

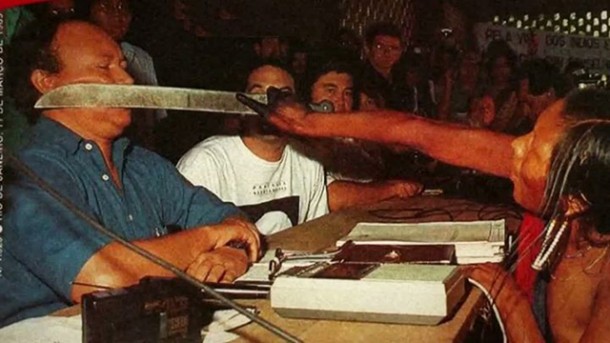

The project was part of Eletrobras’ “2010 Plan” which included 297 dams to be constructed in Brazil by 2010. Though, the project leaked in December 1987, and immediately found the fierce opposition of the public. Especially the indigenous tribes of the region were offered little transparency by the Government, and they gathered to debate the issue in what is known to history as the “Altamira Gathering“, in 1989. During the meeting, a legendary scene was filmed by international television crews: Tuíra, chief of Kayapo tribe and warrior women, with her body naked from the waste up and decorated in black warpaint, ran the blade of her machete three times over the cheeks of José Antônio Muniz Lopes, an Electrobras engineer at that time.

Indigenous chief Tuira shaves Electrobras engineer José Antônio Muniz Lopes at Altamira gathering in 1989

Tuíra´s warfare unfolded in immediate developments, as the World Bank cancelled a $500 million loan to Brazil´s power sector and plans for damming the Xingu were shelved for a decade.

In the meanwhile, between 1989 and 2002, the Belo Monte project was redesigned to be smaller and less invasive. In 2002, Eletronorte presented a new environmental impact assessment of the Belo Monte Dam Complex, which presented three alternatives. Alternative A included six original dams planned in 1975. Alternative B included a reduction to four dams, dropping Jarina and Iriri. Alternative C included a reduction to Belo Monte only. Still in 2002, Workers’ Party leader Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva won the election as President.

In 2008, a new environmental impact assessment was carried out, this time by Eletrobras with the participation of Odebrecht, Camargo Corrêa, and Andrade Gutierrez, which formally accepted Alternative C or the construction only of the Belo Monte dam itself. In the new assessment the dam was also further redesigned, in order to avoid inundating indigenous territory, which is not permitted by the Brazilian Constitution. Still in 2008, José Antônio Muniz Lopes, Tuira’s sparring partner, was elected new president of Brazil´s state electric holding company Eletrobrás.

Indigenous people reacted organizing the Xingu Encounter 2008, a 5-day gathering in Altamira of over 1,000 Brazilian Amazon Indians.

On February 2010, the Brazilian Institute of Environment and Renewable Natural Resources “IBAMA” granted a provisional environmental license, one of three licenses required by Brazilian legislation for development projects. The provisional license approved the 2008 environmental impact assessment and permitted the project auction to take place shortly.

The Belo Monte auction took place on April 20, 2010 amidst the street rallies taking place in major cities across Brazil. Shortly before, Odebrecht, Camargo Corrêa, and CPFL dropped out of the project tender, arguing that the artificially low price of the auction (R$83/US$47) set by the government was not viable for decent economic returns.

Three injunctions, or restraining orders, issued by the Brazilian Federal Attorney General’s Office, suspended the project tender and annulled the provisional environmental license on claims of unconstitutionality. In a few hours, each injunction was overturned by the President of the Appellate Court for ‘Region 1’ – which covers the entire Amazon basin – allegedly succumbing to political pressure from the Lula administration. The auction was held on the very same day, and won by the Norte Energia consortium, by bidding at R$77.97/MWh, almost 6% below the price ceiling of R$83/MWh.

The second out of the three federally required environmental licenses, called the Installation License, was partially granted by IBAMA on January 26, 2011, authorizing Norte Energia to begin initial construction activities. Six months later, on June 1, 2011, IBAMA granted the full license to construct the dam after studies were carried out and the consortium agreed to pay $1.9 billion in costs to address social and environmental problems. The only remaining license is one to operate the dam’s power plant.

During 2011 and 2012, several lawsuits have been filed by Brazil’s Federal Public Prosecutors (MPF), concerning the Belo Monte dam and demanding accountability from the dam-building Norte Energia consortium, Brazil’s National Development Bank (BNDES) and the state environmental agency IBAMA, for noncompliance with mandated mitigation measures. Since then, every verdict which halted the project was soon overturned in another court. The last update is dated September 22, 2015, when Ibama said it would withhold the license until the consortium had completed mitigation projects it had promised.

In the meanwhile though, bulldozers are working. The Indians answered, occupying the Norte Energia office in Altamira on Monday, October 5, 2015.

Read Part II of this article here.