Virtual Reality or VR is something that most people associate with gimmicky 90s sci-fi movies or the gaming industry. But the NY Times as well as other production companies such as LA-based RYOT are showing to the world how VR could change drastically the way we tell stories in journalism.

The idea behind introducing this nerdy trend into the world of rigorous mainstream reporting is not just to make journalism “cool” again in an era when most news are consumed through technology, but also to solve the age-old issue of making people care. Empathy or lack thereof is often a major problem that journalists face when reporting about crisis situations. Readers often find it hard to relate to people that live in far-away, isolated places and humanitarian emergences are not usually met with the social mobilization that the reporters would have hoped for.

This is why the New York Times and other media companies are now exploring the possibilities that VR has to offer. According to filmmaker Chris Milk who released his first VR movie about the Millions March protest in New York, Virtual Reality has the potential to give the viewer a “deeper emotional connection to the people that were actually there”.

Bryn Mooser, producer and co-founder of RYOT adds that

“VR is the most exciting technology we’ve found. It puts people squarely in the shoes of somebody else, so they can see through their eyes and experience the scale of devastation in some of these places”.

RYOT is a production company focused on shedding a light onto the stories that victims of humanitarian crisis have to tell, and bringing them forward to the public in the West to generate a response. They have already released two 360° movies called “Welcome to Aleppo” and “The Nepal Quake Project”, which are both available for viewing on YouTube or on their free app called RYOT VR.

Speaking of the position of social media and big tech companies in regards to this evolution, you know that a trend is going to stick when YouTube, Facebook, Google and Apple have all already jumped on the bandwagon. In fact YouTube is now allowing its users to upload 360° videos onto the platform, which can simply be viewed on the iOS as well as the Android Apps for smartphones and tablets, or in alternative through a newly conceived Google device called Google Cardboard. This headgear is compatible with any smartphone and it is quite literally made out of cardboard, which makes it cheap, easy to purchase and build at home and also eco-friendly; and yet it gives the user a full-on virtual reality experience: what more could a hipster tech-nerd wish for?

Well, for those who have developed a finer taste for visually appealing objects, Facebook is happy to announce their contribution to the trend. Back in March of last year, the social media giant bought Oculus Rift for $2 Billion, a startup developing much more sophisticated-looking equipment to bring VR to the gaming world. Another product that goes in the same direction is called Zeiss VR One, it looks like an upgraded version of the Google cardboard, it works on the same principle but it only supports Apple IPhone devices. Speaking of Apple, they have recently released their first VR video that features the band U2, demonstrating their interest in the emerging sector.

Going back to the effects of this technology on journalism, an interesting initiative has been launched by the New York Times in collaboration with several different artists and film makers. The worldwide renowned publication has been suffering from an overall decline in its newspaper sales, just like many other “old media” news outlets. That is why they decided to launch their very own VR app featuring short documentaries about various newsworthy issues, and to distribute Google Cardboards to all of their home delivery subscribers with the November 7 weekend issue. The media company was one of the first newspapers to publish a photograph and now it wants to lead in this new form of storytelling as well. The videos on the app can be viewed even without the Google Cardboard device and if you want to check out how to do that, you can click here for full instructions. Alternatively, you can get the VR headgear and even cheaper imitations of it on Ebay or Amazon.

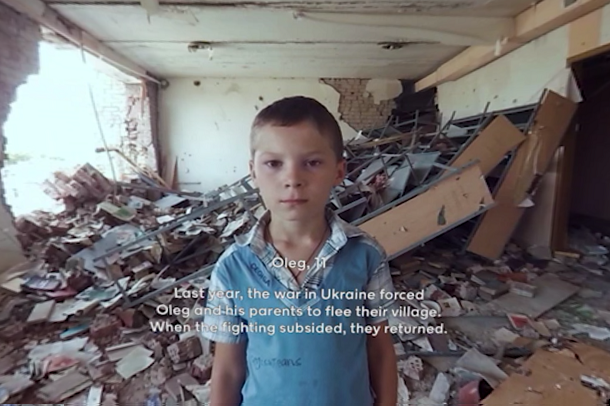

The NY Times project essential revolves around one VR video in particular called “The Displaced”. The 11-minute-long documentary follows the lives of three refugee children who survived the humanitarian crisis in Syria, in South Sudan and in Ukraine. It shows the struggle of their everyday lives and it gives an idea of the state of misery and devastation that affects certain parts of the world. The viewer can move around in the virtual space, discovering new details by himself and feeling more part of the story rather than being just an observer. Many of the watchers reported being touched by the feature in a way they likely wouldn’t have been by a traditional photo series in the printed newspaper. The short film has been described as an “empathy machine”, and perhaps it could represents a way to bring people together in an effort to provide for a better future for the most innocent victims of recent wars.

This technology offers a new exciting perspective to a forever-evolving sector such as the media industry, but critics warn against possible ethical issues that might emerge in the process. Some are skeptical about the costs of producing such videos, which can amount up to $100 per minute, saying that big media companies will have a natural advantage and end up wiping out all the smaller publications that had found a platform thanks to the internet. Another major issue seems to be that the movies are filmed using multiple cameras and complex techniques so certain scenes need to be shot several times and be heavily directed by the producers, which takes away much of the “reality” component from the shoot. Finally, the lack of framing by the journalist might also be problematic, as Fergus Pitt, analyst at the Tow Center for Digital Journalism, points out:

“It’s certainly fair to ask whether VR – with its more realistic depictions – might be more deceptive [than other forms of journalism]. Audiences, when asked, will say they understand that journalists crafted the work, but the scenes they’ve watched will stay lodged in their minds and maybe their subconscious in a powerful way. That’s a serious responsibility. […] The pretense of VR is seeing something that actually happened as opposed to something obviously constructed, so authorship is more blurred”.

Many supporters of this new technology reply that “there is a whole host of ethical considerations and standards issues that have to be grappled with”, as in the words of Will Silverman, journalist at the NY Times. And yet tackling this ethical issues as well as developing guidelines and common understandings of what techniques are acceptable could grant VR the role of new and exciting, yet still legitimate journalistic tool.