RGNN recently published this article about why awareness of art culture matters in the 21st century, but there are those who remain unconvinced. Let us now look at outsider art: a term that is also a counterargument to the idea that art lovers and artists need to know about art culture in order to contribute to it.

The spirit of outsider art is that of counterculture. It resists the conventional limits of what we call “art”. We can most clearly define outsider art by what it is not: not conventional, not fashionable, and completely untouched or at a distance from by the methods and trends of contemporary artistic culture.

Graciela García is a researcher for for the Galerie Christian Berst and Art Brut Project Foundation, and author of the blog “El Hombre Jazmín” and the book Arte Outsider. La pulsión creativa al desnudo Outsider Art: The Creative Pulsion Uncovered], which explores outsider art within a Spanish and international context. She writes on her blog that outsider art in Spain “refers to the creations that escape, countercurrent to the homogenization of Art. Its protagonists are people, mostly self-educated, that experienced an irrepressible need to create,.

The Collection de l’Art Brut in Lausanne, Switzerland, currently has the largest collection of outsider art in the world. Its low, intimate lighting and boundary-pushing exhibits create an atmosphere of pure theater. It is a relatively small museum of three floors, but one visit is not enough to fully appreciate this gem. Its rotating exhibits make the Collection de l’Art Brut a necessary stop every time I’m fortunate enough to visit western Switzerland. For those of you in Spain who, like me, don’t have a trip to Switzerland planned in the foreseeable future but still want to appreciate outsider art, the following are three internationally recognized Spanish artists who embody its unconventional spirit.

1. Josep Baqué (1895-1967)

Josep Baqué. Untitled, between 1932 and 1967 – pencil, ink and gouache on paper – 26 x 32.7 cm | Scanning Workshop, City of Lausanne / Coll

Josep Baqué. Untitled, between 1932 and 1967 – pencil, ink and gouache on paper – 26 x 32.7 cm | Atelier de numérisation, City of Lausanne

Baqué compiled a bestiary: 454 plates comprising 1,500 vivid drawings of imaginary creatures and animals, which he meticulously sorted into nine categories: animals and wild beasts, primitive men, bats and insects, giant spiders, snakes, snails, octopi and cuttlefish, feathered animals, and diverse fish. Baqué’s winged, fanged, and many-legged fantastical creatures delight in the blurry line that separates the monstrous and the beautiful.

Baqué was born in Barcelona. Baqué was well exposed to the decorative arts before leaving home at the age of 17. He worked in France and Germany before being drafted and obligated to return to Spain in 1914. From 1928 to his death, he worked as a police officer in Barcelona..

Fifty plates of Josep Baqué’s work belong to the Collection de l’Art Brut in Lausanne, Switzerland, where they are regularly displayed in rotation.

2. Joaquim Vicens Gironella (1911-1997)

![Joaquim Vicens Gironella. Le pont Valentre, Cahors, [Valentré Bridge, Cahors] between 1941 and 1997 low-relief of carved cork in a black wood stand - 63,5 x 95 x 2 cm. | Collection de l’Art Brut, Lausanne](https://archives.rgnn.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/Joaquim-Vicens-Gironella-One.jpg)

Joaquim Vicens Gironella. Le pont Valentre, Cahors, [Valentré Bridge, Cahors] between 1941 and 1997 low-relief of carved cork in a black wood stand –

63,5 x 95 x 2 cm. | Collection de l’Art Brut, Lausanne

Gironella was born into a family of cork makers in Catalonia near the French border. After fighting on the Republican side of the Spanish Civil War, Gironella went into exile in 1939. After a year-long period of internment in Aude, France, Gironella took up work at a cork factory in Toulouse, France, upon his release. He began carving cork in 1941, and thereafter continued to focus on his writing and sculpting cork

Joaquim Vicens Gironella’s work forms part of the initial core of Jean Dubuffet’s Art Brut Collection on display at the Collection de l’Art Brut in Lausanne, Switzerland.

3. Miguel Hernandez (1839-1957)

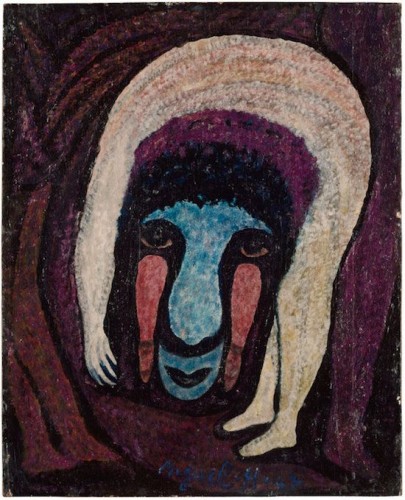

Miguel Hernandez. Untitled, 1947 – Oil on wooden panell – 41 × 33 cm | Collection de l’Art Brut, Lausanne

Miguel Hernandez. Untitled, 1947 – Oil on wooden panel – 41 × 33 cm | Collection de l’Art Brut, Lausanne

Hernandez’s work is characterized by highly stylized depictions of women, birds, and images of the working class in Spain. The agitated spirals and warps in Hernandez’s paintings and drawings create ghostly profiles, stretched limbs, and strange faces distorted by a darkly inhuman, fantastic air.

Born into a family of peasant farmers northwest of Madrid, near Ávila, Miguel Hernandez—not to be confused with the poet of the same name– was a completely self-taught painter. He emigrated to Brazil at the age of nineteen and worked in several trades before returning to Europe. After his return, Hernandez was arrested several times in Spain and Portugal for contributing to anarchist and anti-militarist propaganda. Upon his return to Spain, Hernandez fought as an anarchist on the Republican side of the Spanish Civil War, after which he fled into exile. In Paris, Hernandez lived in poverty but continued his artistic work and political work as the director of Free España newspaper.

Miguel Hernandez’s work forms part of the initial core of Jean Dubuffet’s Art Brut Collection on display at the Collection de l’Art Brut in Lausanne, Switzerland.

Is there another Spanish artist you’d like to recognize? Tell us about it on Twitter @ROOSTERGNN.