Roughly two centuries ago, the industrial revolution that started in Victorian Britain completely changed the way people live, work, commute from one place to another. Another cultural wave with far-reaching impact rose as a vigorous yet elegant response to the rapidly industrialized world cramped with machinery and factory production: the arts and crafts movement emerged to restore aesthetics and spirituality to a society filled with an appreciation of beauty without intelligence. W. R. Lethaby summarized the idealistic nature of the movement in his book entitled Architecture, Mysticism and Myth as follows, “the message will be of nature and man, of order and beauty, but all will be sweetness, simplicity, freedom, confidence, and light.”

Art For All

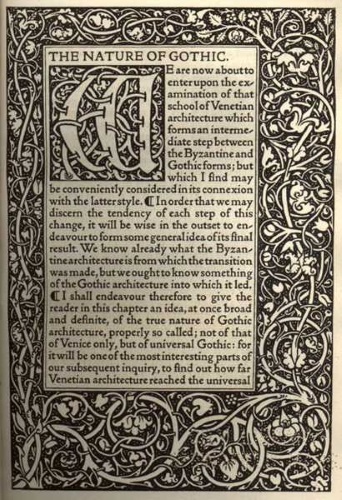

“The Nature of Gothic” | William Morris, Kelmscott Press, 1892

It would be misleading to believe this international movement was the result of spontaneous enthusiasm for art or hatred for the modern society, rather, the arts and crafts movement rested largely on the gothic root that dates all the way back to medieval age. Highly spiritual it was, Gothic on the other hand serves as an iconic combination of artistic creation and practicality.

It is interesting to note that many figures that were devoted to this movement were also socialists. The movement was therefore also a way to achieve the socialists’ vision of making decorative commodities available to possibly everyone in the society.

Freedom of Creation

The arts and crafts movement was a compromise between craftsmanship and high art, a heated debate that has been haunting artists since Renaissance. For those art theorists, architects and artists in favor of this movement, artistic value and craftsmanship are one. In order words, to become an artist one must first be a craftsman. Moreover, though characterized by its fluid, free-flowing forms that drew their inspiration from nature, the freedom to create decoration arts was, nevertheless, beautifully bounded by practicality.

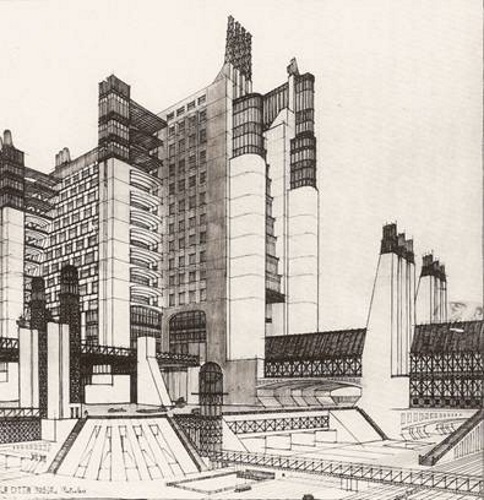

Though supported by a group of leading figures with an idealistic vision of rejecting the cold hard mechanized world to one that draw inspiration from nature and folk culture, the romantic tale failed to realize and technological advance continued. Futurist architects like Antonio Sant’elia might be happy to see that his sci-fi cityscape imagination is finally coming to life.

La Città Nuova (The New City) | Antonio Sant’elia, 1914

Today, we have already entered the Fourth Industrial Age where the labor size shrinks by large and much of it is replaced by machines. Many of the machines are backed by artificial intelligence that they are automated and even inter-connected, they can perform analytics based on the data available. Many suspect that it is only a matter of time that these machines develop their own thoughts and will, and eventually break away from the control of human.

At this point, it seems we are once again teased by history. If one recall the social response to the first industrial situation back in the late-18th to mid-19th century, it was also split into two distinct camps. One side embraced the progress, speed and new possibilities, while the opposite side was more of romanticists filled with nostalgic sentiment.

Moreover, artistic creation is no longer a special privilege to human because lifeless machines can also compose sweet melodies, tell affectionate stories with poetic words, or create a sculpture that is obviously a result of precise calculation. This is where the terror grows, precisely, what will be the future of the entire human race if machines can breakthrough even our last defense, human creativity? For our generation, this is one of the major humanitarian issues that one must contemplate on. This time, a neo-arts and crafts movement that is improved upon the last one is what we need. If the development of civilization is a circular path that we must embark on, then history certainly helps by allowing us to meditate on it before we move forward blindly.

The Morris Dilemma

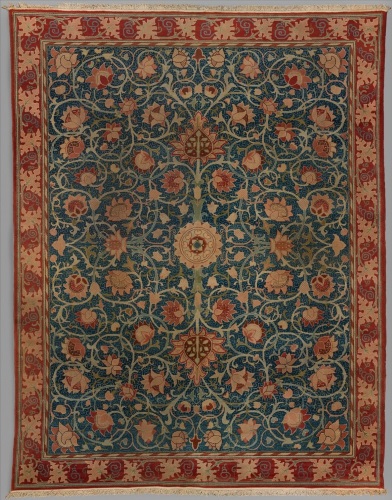

Holland Park carpet | Designed by William Morris, late 19th century, Wool and Turkish knot, 515.6cm x 396.9cm, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, U.S.

The first and foremost criticism this movement received can be summarized as the “Morris Dilemma.” The textile design, poet, novelist and socialist activist despised the modern industrial world and industrialization that he entirely rejected the use of any technology or machine to create art work, instead, a large labor forced was employed to restore the roughness to decorative art. As his products became widely accepted and popular, production size increased drastically. Eventually, even to Morris’ surprise, his socialist vision turned into the nastiest reality that an idealist that dwelled in the beauty of artistic creation would never wish to face: a large group of cheap labor mass producing goods that are only affordable by the rich. The arts and crafts movement under his command became a craftwork factory, it was no longer running against the flow of industrialization that had disgusted Morris so much, but flowing along with it!

Art Needs a Solid Base

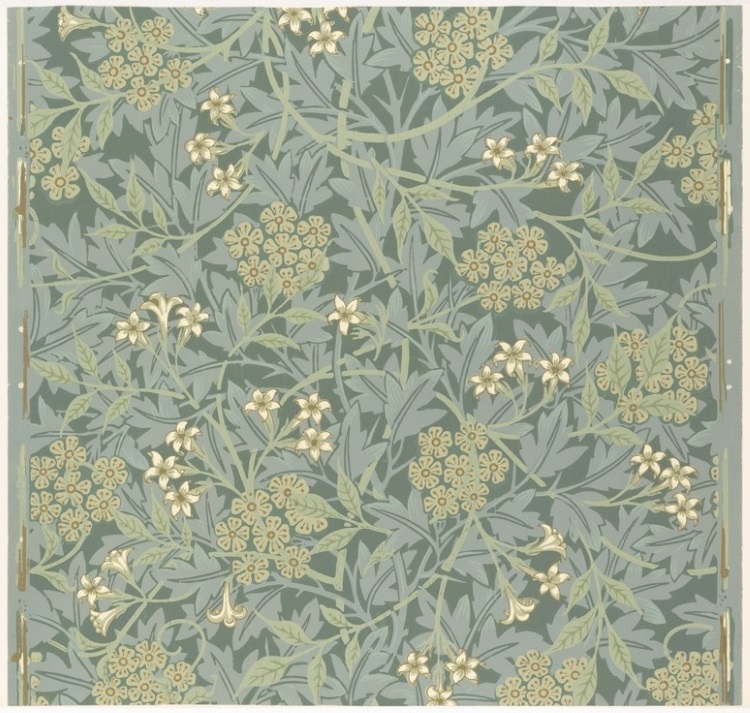

Jasmine | Designed by William Morris, 1872, Block-printed wallpaper, 54.5cm x 57.2cm, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, U.S.

Another view that Morris held strongly was that art was the only means to save the industrialized modern society, from both the hands of capitalists and machines. True, a world without art would be too miserable to even imagine. While his design influence was widely received by the public, the idealist soon found an obvious contradiction between the ideal of democratic art and the “idle privileged class,” who were also his major art patrons. Eventually, Morris’ decorative art production turned into another labor-intensive manufacturing process.

It is no doubt that art has its essence, it could be elevated even to a speculative metaphysical extent. But time and again what the history of art tells us is that art did not rose to such height by itself against the law of gravity, as an inherent trait. Nor is it as omnipotent as nature that it sustains itself through centuries. Art needs support from a solid financial foundation.

Boundless Creation

Same as Ruskin, Morris also shared the fascination for the roughness of handcrafts, this was why his art production required so many labors when the demand soared. In today’s era of machine automation, it is almost impossible to reply on labor to perform such highly demanded decorative art products, not to mention we are not wired to perform tasks with high precision like machines do. Apart from craftsmanship, many values of artistic creation come from the spontaneity and randomness that are unique to human creativity. It is this explosion of emotions, be it subtle or intense, that draws viewers into the artwork.

Though machines are powerful, there is nothing to be afraid of. Their power largely rests on big data and analytics, which would inevitably stop at prediction based on past events. Rather, machines can even be another tool that helps with artistic creation, only by doing so can artists devote more time to their ideas and experimentations with different medium and tools, with technology being one of many.