The movie Crazy Rich Asians has reportedly earned $171 million so far, according to Box Office Mojo, a website with one of the most comprehensive box office data bases on the Internet. But perhaps more importantly, the film featured the first inclusive all-Asian cast in 25 years, earning the title as one of the most groundbreaking features of the century. However, beyond the United States, the movie didn’t fare as well.

Before Crazy Rich Asians, the last Hollywood film to feature an all-Asian cast was Joy Luck Club. Between these two movies, Asian representation in films was pretty much either non-existent or worse; white-washed. Naturally, much expectation was given to Crazy Rich Asians when it was first announced. Yet of its total earnings, only 26.4% were made internationally.

Why is that? The short answer: Crazy Rich Asians does not represent reality. Let me tell you, I am a native East Asian.

Reason one: Crazy Rich Asians did not capture the essence of an East Asian household, or rather more specifically, a Singaporean-Chinese household. While the book used the imagery of a Singaporean-Chinese mother walking her children to their destination even though it was raining cats and dogs, highlighting the importance of frugality in the culture regardless of one’s wealth, the film used the hotel scene as an appetizer to the audience’s journey of discovering the true worth of the young family fortunes. It was as if the representation was done for representation’s sake – the Hollywood touch to this film has counteracted the purpose of its story.

For East Asians, the film was a letdown.

So much that would have resonated with our childhood and our upbringing was thoroughly erased away by Hollywood, and such sentiments were replaced by its rom-com theme and washed-down versions of what really happens behind closed doors, and what drives feuds and breakdowns within Singaporean-Chinese families, crazy rich or not.

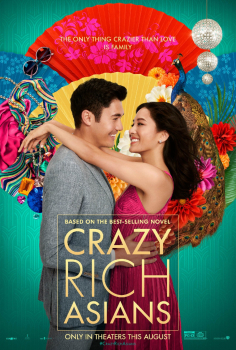

Crazy Rich Asians | Official movie cover

On that note, the film has also neglected to highlight the Singaporean ethnic makeups. Prior to Singapore’s independence from Malaysia in 1965, it was the state where immigrants from the southeastern coast of China chose to settle in. The fact that it was so heavily populated by the Chinese was the reason why they became their own country. Nevertheless, the country’s roots were Malaysian, where three dominant races (Malays, Indians and Chinese) live harmoniously.

While there is absolutely nothing wrong to focus on a certain ethnic group, it is the fact that the film industry has long neglected to present Asians beyond ‘model minority’ and basically socially unsavory, that has made the problem of representation an even trickier issue to solve. Before the Western world can even wrap its head around how diverse “Asianess” really is, here comes a movie that has misdiagnosed the real problem behind Asian representation and has used the word “Asian” in Crazy Rich Asian as generously as how the word “African” has been historically used. To put it simply, the world is not ready to accept non-White film representation is either niched or specific to a certain group of people.

Moreover, the plot was heavily stained by female rivalry which begun unfolding five minutes into the film. What was perhaps more appalling was when Golding’s character reassured that the American-Asian girlfriend was not as materialistic as the girls he used to know. Again, the problem is not building Nick Young’s story on the weaknesses of human character, which in this case is materialism of Nick Young’s past female acquaintances. The problem is that there is a practice to lump a ‘minority’ group into a box, and the danger is if people use this film, of which the Singaporean author was heavily involved in, to justify further stereotyping of Asian-born women.

Perhaps the most uncomfortable part of the film was the Singaporean actors’ unnatural accent. Beside Pek Lin’s mother, every other born-and-raised Singaporean characters seem to either have an Americanized accent or a somewhat-British accent. A great example would be Michael, Astrid’s insecure husband and even Oliver, the character we all love. Singapore is known for its lax use of the English language, termed as “Singlish” (Singaporean English). Due to its multiculturalism that is unique to Singapore and Malaysia, communication is done through stringing words and verbal expressions from the different languages used in the country. It is engrained in our culture. Was it perhaps these actors were pressured by the fact that the film is Hollywood? If so, why weren’t they advised against it since the movie was set in Singapore, made about the Singaporean-Chinese culture?

Asian-born Asians, at the end of the day, are quite different from Asians born abroad, as the film pointed out. The high hopes we have put on the film to spotlight our way of life were disappointed also through the unrealistic physicals of the main cast. Instead of casting Asian-born Asians, they chose to Hollywood-fied Singapore, as if to say non-mixed race people and born and bred Asians are less attractive then actors such as Henry Golding, who is half-Iban, half-British white, and Gemma Chan, who is British by nationality and Chinese by ethnicity. This poses a problematic representation, simply because it isn’t representative at all. An all-Asian cast should not be limited to Asians born and bred abroad. If representation is what we are aiming for, then Hollywood really has to look beyond their rolodex.

Crazy Rich Asians may be a breakthrough, but it is a premature breakthrough, and one only limited to Asian Americans and British Asians. The problem with Asian representation is not so much with volume these days. Of course, with that being said, it wouldn’t hurt for more roles to come up. The real problem is the ancient practice of typecasting and whitewashing. Crazy Rich Asians may have solved the first layer of problematic Asian representation, but the intrinsic issue was much neglected.