ACCRA, GHANA. Their marriage exemplifies struggle and success. She rests on his shoulder, her slender body covered in a long yellow and green patterned dress, smiling to her surroundings. He stands beside her, hands clasped behind him, smiling down at her. Their illnesses are washed away with their love, but are also part of their love. Langa Amadu, the Northern Regional Secretary of the Network of African People living with HIV/AIDS (NAP+), and his wife, Adiga Sulemana, are HIV-positive. They live in Dr. David Abdulai’s Shekhina Clinic in a suburb of Ghana’s third largest city and northern regional capital, Tamale.

Dr. David Abdulai at his Shekhina Clinic in Tamale

Living outside the clinic wasn’t easy for the couple. “It’s a great challenge with stigma and discrimination – that’s why we are here,” said Amadu. Prior to arriving at Dr. Abdulai’s, people refused to meet with Amadu for fear of being associated with HIV/AIDS. But today, home life provides solace for Amadu, his wife, and two children, both HIV-negative.

Another HIV-positive patient living in the clinic, Abdul Rahman Abdul Aziz, agrees with Amadu. “I prefer it here,” he said. Aziz, who laughs easily when speaking about his life, came to the clinic from his native country, Sierra Leone, where poverty is more striking than in Ghana, where over 40 percent of people live on less than $1 a day.

Abdulai’s clinic is home to some of West Africa’s destitute and physically and mentally ill, including four HIV patients.

But throughout the rest of Ghana, and for the 230,000 individuals, as estimated by UNAIDS – a population comparable to Jersey City – living with HIV/AIDS can mean one thing: stigmatization.

Alex Boakye, of the West Africa AIDS Foundation here focuses his work on stigma reduction. Boakye spreads information through demonstrations and presentations in schools and churches throughout Accra. And while Boakye believes that most people in the region know they should not stigmatize HIV/AIDS patients, many still do. In his presentations, Boakye poses a question about whether or not a person would still marry a person, regardless of how smart, kind, or rich that person was, if that person was HIV-positive. “The reality is that about 70% of them would say ‘no,” he said.

But potential spouses are not the only ones who create the stigma attached to the virus. “We also realize that their families are making matters worse in the sense that once they know their status, they begin to relate to them in a certain way,” Boakye said. Because of this, the patients begin to self-stigmatize, distancing themselves from their friends and families. And it doesn’t stop there – when the person tests positive for HIV in Ghana, the reaction of the doctors could contribute to their feelings of loneliness.

According to Dr. Naa Ashiley Vanderpuye-Donton, the executive director of the West Africa AIDS Foundation, this in-clinic stigmatization is even worse for Ghana’s gay community, commonly labeled MSM (men who have sex with men), which makes up a large chunk of Ghana’s HIV-positive population. While many clinics in Ghana parade as gay-friendly, “Health care workers still want to change their lifestyles,” Vanderpuye-Donton said. Because of this, people don’t get tested, and the virus spreads.

The discrimination of LGBT identifiers is rooted in Ghanaian culture, where religion is found on every street corner. While churches and mosques throughout Ghana are becoming more open to HIV/AIDS patients, the same cannot be said about the gay community, and especially those with HIV/AIDS. “It’s very difficult to talk about MSM with spiritual leaders in the churches. We’re not supposed to talk about it. It’s a sin.”

This “sin” mentality is spread throughout Ghana. “It is our cultural and traditional setting that has classified that particular act as an abomination. So those types of people are not accepted in the society,” said Nat Nuno-Amarteifio, the former mayor of Accra.

Handprints of patients and their children outside of the West Africa AIDS Foundation

The not-so-friendly clinics only dissuade patients further from seeking treatment. Dr. Henry Nagai, the country director of Family Health International (FHI) 360 Ghana, says trying to convert patients to have a religiously and culturally acceptable sexual orientation doesn’t work, and ends up doing more harm than good. “It is about upholding the rights of that minority population. It is the ability to live in their communities. Irrespective of our cultural, tribal, secular beliefs, it is to trample on the rights of a person to not allow him or her to have healthcare services available to the general population,” he said.

But HIV/AIDS rates among LGBT patients in Ghana may be higher than perceived. The reasoning is simple – gay patients are scared to get tested. “Most people cannot come out of that community,” said Mac-Darling Cobbinah, the director of the Centre for Popular Education and Human Rights in Accra. “LGBT people are automatically highly stigmatized because the issue is taboo in Ghana. They live underground; their lives are not seen openly,” he said.

According to UNAIDS, an estimated 15,000 people die of AIDS annually in the country, leaving 180,000 Ghanaian children orphaned.

Stigmas attached to the virus are also linked to religion in Ghana, which drives both personal and professional life throughout the country. According to Cobbinah, HIV was originally considered a death sentence, and therefore, many believed it to be a disease from God. “Since most people are Christians and Muslims, the stigma is very high within the community,” he said.

Professor Kodjo Senah, of the University of Ghana Legon Sociology Department, agrees that stigmas attached the HIV/AIDS come from the original idea that it testing positive meant death. According to Senah, churches tried to distance themselves from HIV patients because they would lose parishioners if others found out that others within the church were HIV-positive. In Ghana, where more than two of three people are Christian, finding another church is easier than finding a supermarket. Still today, even though churches are providing education about HIV/AIDS, the stigma remains strong. “People will not run away from you, but they will not sit close to you,” Senah said.

Langa Amadu with his wife Adiga Sulemana, outside their home in Dr. Abdulai’s clinic

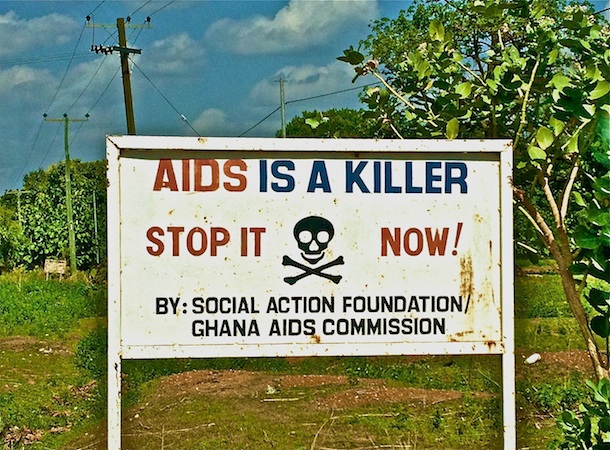

And yet, although stigma still permeates society, awareness has increased. Billboards and road signs throughout Accra encourage people to get tested for the virus, and Ghanaian government officials have identified HIV/AIDS as a major concern.

Two hundred seventy miles north of Accra, in Dr. Abdulai’s clinic, where Amadu, his wife, Sulemana, and Aziz live, stigmas attached to HIV/AIDS don’t exist. Abdulai, who attends church regularly, and attributes the clinic to God’s will, does not consider an individual’s sexuality when admitting them to his clinic. “It would not be of concern to me because he is a human being who is sick and needs my help.” Instead, Abdulai says that one item fuels his clinic and his healing of all people – regardless of sexuality or religion – “Our primary commodity here is love.”

Back in Accra, Senah’s knowledge on the stigmatization of HIV/AIDS in Ghana comes with a personal perspective. His cousin’s daughter, he explains, was recently tested HIV-positive. When his cousin consulted him regarding her daughter, he advised her not to tell anyone, explaining that she could lose friends, her job, and even her home. “Indeed if you have AIDS, all others around you will be stigmatized,” Senah said. “So you have to keep the disease to your chest.”

– Katelyn Israelski