MIDDLE EAST. Tylenol to cure a headache and an aspirin to fix the runny nose – today’s modern

medicine is often direct and quick in relieving patients of their painful symptoms. But

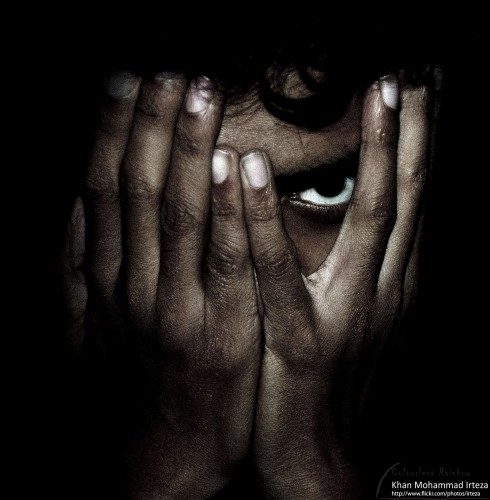

what happens when the solution is not as simple? Depression, a common dilemma found

in Western societies, has finally bared its ugly face in the Middle East where its

skepticism is at an all time high. A report by the Mental Health Foundation explains on

how society “has stereotyped views about mental illness and how it affects people.” These ‘stereotypes’ are generally focused on the severity of mental disorders.

Perhaps the lack of recognition concerning mental health in Middle East has lead to insufficient treatment. In fact, many patients suffering from mental illnesses are often subjected to further isolation based on the medical attention they receive. A study published in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry called attention to the “large gap” in the Middle Eastern population among those who need treatment and those who actually receive treatment for depression. The report highlighted the distressing fact that most victims of mental disorders often suffer in “silent” isolation, without proper outlets provided by government or healthcare officials. Moreover, the World Health Organization remarks on the “ [inadequate] treatment” of “more than 75% of people with depression in developing countries.”

As a 2013 study conducted by the Public Library of Science determined, “more than five per cent of total population situated in the Middle East, North Africa, and the Sub-Saharan Africa have depression.” However, researchers are still baffled when it comes to determining the root cause of this unexpected rise in depression. Liyam Eloul, one of the main contributors to Silent Epidemic of Depression in Women in the Middle East and North Africa Region (published for Sultan Qaboos University Medical Journal), argues that Western ideations illustrate depression as a force which exponentially grows due to the fact that “Islamic beliefs and practices exacerbate stress and distress in women.” However, this notion is often considered controversial and is debated against on the grounds that misogyny is a global issue – one that may be fueled by religion but it is certainly not ignited by it. Another possibility stated by the International Medical Corps deems “daily stressors” as the partial responsible party for the rise in depression. For instance, Syrian refugees label those with pre-existing mental health disorders more “[pre-disposed] to develop a specific mental health illness.” Trauma of war coupled with an instable environment increases the frequency of disorders appearing in Middle Eastern societies. Unfortunately, inadequate treatment is still an issue: only “a small number of refugees are receiving some form of mental support from the United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR).”

The United Nations High Commission for Refugees reasonably judges that the focus and

aid should be on basic needs, once again leaving mental patients in an isolated atmosphere

where their disorder is not regarded of great importance. The problem lies in society’s

failure to recognize depression as an emerging fatal flaw in modern Middle East. Without

recognition of the problem and proper treatment how can the Middle East aim to cure

depression’s rapid growth in society?