`ñI live in Belgium since 4 and a half years. I am well integrated in Belgian social and political life, and I am taking part to the local initiatives against the steady deterioration of living conditions resulting from increasing welfare cuts.

Austerity measures have been challenging people’s basic rights across the EU indiscriminately. But the extent to which this is negatively affecting people’s everyday lives – and their thinking/stance about what is going on – mainly depends on how much developed is their welfare system. People in Belgium are (still) used to receiving high-level standards of social benefits.

This is the main reason why many people around me seem not to be concerned about the current negative trends. Recurring reactions to my insights are “I don’t like talking politics”, or “you’re radical”. This can also explain why people stare at me and think I’m kidding when I explain to them that being ‘disoccupato’, (‘chomeur’, ‘unemployed’) in Italy does not imply being entitled to some kind of economic assistance from the state. This term merely describes a situation of joblessness, which in most of the cases is synonym for poverty.

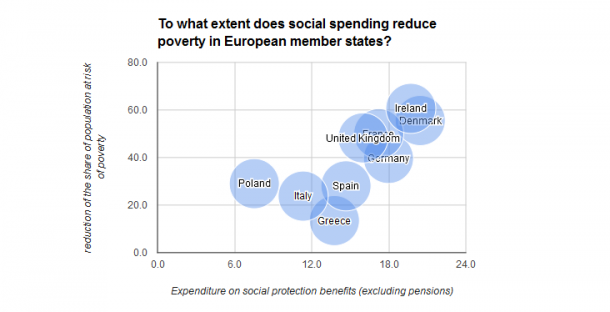

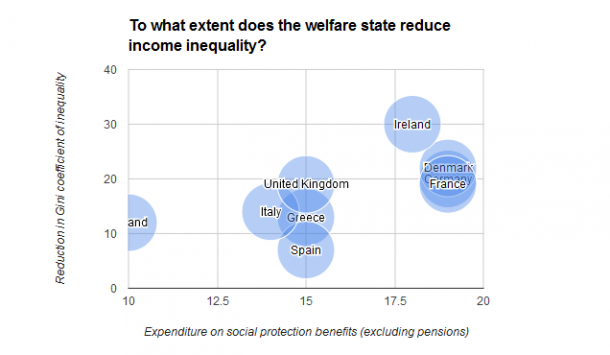

Italy is one of the EU countries where (ever-decreasing) expenditure on social benefits doesn’t help reducing poverty and inequality. The main ‘social benefits’ in my homeland are a function of your family’s efforts and if you’re good enough in the widespread arte dell’arrangiarsi. Do it yourself. Reacting to the absence of the state with your (desperate) creativity.

We are champions in unemployment trends though, and we keep on performing better and better on this.

Good news: hitting rock bottom also helps preparing the ground for an increasing public support for useful measures (and this is not the only example you will get here of Italians’ positive attitude in facing life). Indeed, in May 2015, nearly 50 thousand people took part to the 24km-long March for a Citizen’s Income in Central Italy.

The basic assumption underpinning this proposition is that every single citizen in the age of majority should be entitled to nearly 800 euros per month. This is, of course, ‘revolutionary’ in a coutry like mine. I wholeheartedly agree with this kind of measure. Italians had to wait until ordinary citizens entered the realm of mainstream politics to finally see politicians discussing on how to address the country’s overall economic conditions. That said, this is a quite vague proposal as regards the implementation process and adds confusion to political language, concepts and also potential outcomes.

The proposed Citizen’s Income in Italy is actually a kind of unemployment benefit, entirely conditional to availability for work or some kind of commitment to a reintegration trajectory. (My dear friends from Belgistan, yes: we are struggling to have recognised the same right that you have been using without even noticing it. And that current cuts urge you to finally notice it).

The proposition for a guaranteed minimum income finally landed in Parliament after a popular initiative collected 50.000 signatures. Surely this initiative can represent an important contribution to poverty alleviation in Italy and may also help determine some specific aspects of the welfare reform.

Elsewhere in Europe and beyond, the hot issue is the Universal Basic Income, which is quite a different thing. It is a right granted to every person, on an individual basis, independent on any preconditions (like the willingness to take up paid employment), not subject to income, savings or property limits, and high enough to ensure a life in dignity. It is conceived as a measure that supports the realisation of fundamental rights.

There is a significant difference: the Universal Basic income is entirely based on the idea that we should decouple income and labour. Why? Because economic growth is less and less dependent from labour, and more and more dependent from technological innovation. Because we must stop running behind GDP growth and give us a chance to review balance between work and other pursuits in life. Because we ended up slaving away to get food and afford the rent. Because, finally, most social protection systems, whether sophisticated or not, are failing to address their main objective: prevent poverty, while creating time- and money-wasting bureaucratic bodies.

There exists a glut of university graduates whose skills are too often laid to waste in dead-end jobs and seemingly endless spates of joblessness, many of whom could well possess the skills necessary to boost the continent’s recovery.

Barb Jacobson, European Citizen Initiative for an Unconditional Basic Income

Discussions on how this constitutes a strong disincentive to work should take into account studies and experiments undertaken in this respect; for instance, the so-called Mincome Programme, run in Canada between 1974 and 1979. The aim was to ascertain whether or not guaranteed income would inhibit productivity. The results showed that only two groups were affected negatively: new mothers, who spent more time with their children, and teenagers, who were fully immersed in studies and further education. As for financial feasibility: the ‘where-do-we-find-money’ approach is usually symptomatic of the total lack of interest for a meaninfgul political discussion about something.

The ECI for an Unconditional Basic Income, launched in 2012, did not reach the minimum requirements foreseen by the treaties. However, it is a valuable idea that is still inspiring community efforts in several countries at different decision-making levels.

For instance, next year Switzerland will hold a vote on whether to implement a basic income of 2,500 francs per month for all citizens. And this is not the country’s first attempt to redress the balance. The Dutch city of Utrecht is about to experiment some basic income payments starting from January. These and other examples are an indication that change is already underway. And yes, that I’m radical, too.