To start with, it is necessary to identify the differences between being erotic and being sensual. According to Merriam-Webster, sensual relates to the gratification of senses, with the indulgence of the physical appetites as an end in itself. Whereas erotic describes the arousal of sexual love or desire. Though eroticism seem to be a more explicit state of sexual excitement, it is nonetheless much more complicated and confusing. Eroticism does not necessary require visual nor sensory experience as trigger, rather, it is more dependent on mental activities. Consider the example of reading erotica literature, it is not the ink on paper that arouses our sexual imagination, but the meanings behind, which are interpreted by us. On the other hand, sensory experience is required for one to feel sensual. Hence, although theoretically, sensuality can and does oftentimes arouse erotic feelings, it is not necessarily always the case.

Putting sensuality in the context of art, German scholar Eduard Fuchs praised it as the highest and noblest purpose of art, whose ultimate aim was to delight rather to instruct. Such opinion was shared by Hegel, who considered using art as a tool to narrate, demonstrate or preach an act of deflating the purity of both the ends and the means. The femme nouvelle in Alphonse Mucha’s commercial posters during La Belle Époque in Paris was thus hence sensual, rather than erotic, such is demonstrated in the artist’s choice of medium and the role of women in his posters. He was a romanticist that believe in the power of art to create a better mankind, and deep down a devoted patriot for his nation, Czechoslovakia.

More Than a Commodity

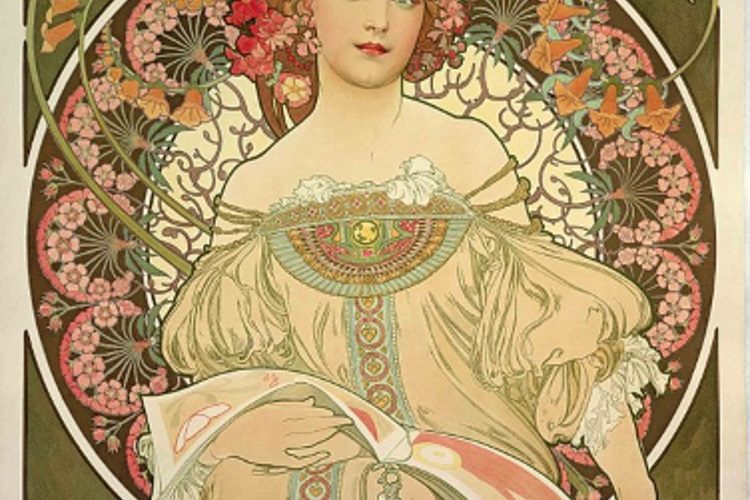

Alphonse Mucha, The Arts: Dance, 1898, Color lithograph, 60cm x 38cm | Wikimedia Commons

Very much inspired by the Arts and Crafts Movement that first took place in Britain, Mucha’s choice of female figures as the subject of most of his commercial works originated in the artist’s celebration of feminism as an antidote to an overly-masculine, impersonal and mechanized world. Mucha’s women was thus seen as a restoration of aesthetics and beauty to a commoditized world by both the painter himself and his peers.

The romanticized appraisal of these beautifully depicted life-sized female figures was characterized by their smooth and fleshy skin, swirling hair, occasionally half-invisible and floating Bohemian-style dress, which all convey a sense of sensuality to the mass public. These visually appealing women were not a commodity to be objectified nor sexualized by male viewers as in the past, rather, they were elevated aesthetically. The femme nouvelle became a symbol that moves our free soul, yet avoid touching upon some of our most secretive mental activities.

Masculinity vs. Feminine

Johannes Vermeer, Young Woman with a Water Pitcher, ca. 1662, Oil on canvas, 45,7cm x 40.6cm, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, U.S. | The Met Public Domain

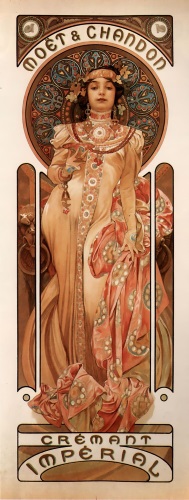

Nonetheless, Mucha’s women, though tender, were oftentimes used to advertise commodities that are traditionally related to male, such as cigarettes and wines. It coincides with the fact that at the turn of the twentieth century, new sets of gender roles began to took form and the boundaries that used to distinguish between male and female were blurred. It was an era when sexual liberty was praised and sensitive topics like homosexuality were debated. Women were also no longer the quiet and obedient maidens depicted in Vermeer’s household paintings, but they began to vote for their own political rights and receive education.

While some at that time embraced the idea of New Women and consider them somehow sexy, many still considered it daunting, if not immoral. Most male intellectuals believed that the gradual removal of gender boundaries between male and female was equivalent to sexually degenerate, and was one of the many fears that contemporaries had for the turn-of-century. It is understandable that for male, it should be hard to attach sexual feeling with these monstrous females performing “masculine activities” in their eyes, who, despite dressed in floral and astral wrapping, were no different from hereditarily-ill and inferior beings.

Strength and Confidence

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, Judith Beheading Holofernes, ca. 1598-1599, Oil on canvas, 145cm x 195cm | Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Antica, Rome, Italy

The rise of social status of women in the late 19th century boosted their strength and confidence, which in the past, it usually they were related to women in much of a negative way.

Tracing back to paintings in the Renaissance, one of the most powerful strength that lies in female was revenge and seduction. For the latter, female was perceived as an evil being that manipulates men with their bodies, that fool men and prevent them from making rational judgments with their pure and innocent virginity, when deep down women were extremely sexual and even lacked the ability to control their inner desire. This was also prominent among modern painters, such as Edvard Munch and Gustav Kilmt.

Edward Munch, Madonna, 1894, Oil on canvas, 90cm x 68cm| Munch Museum, Oslo, Norway

Both captured the female figures’ state of being sexually aroused. Munch attached the erotic state to a more negative meaning by surrounding the nude female figure with bold and circular brushstroke of dark colors. Whereas Kilmt, who attempted to break away from and challenge established morality/ ethical values in the Viennese society, praised this moment with golden and floral decorations, the former as symbolic meanings derived from the Greek mythology.

Gustav Klimt, Danaë, 1907-1908, Oil on canvas, 77cm x 83cm | Leopold Museum, Vienna, Austria

Once again, though sensually depicted, male intellectual and elites probably had more fear than desire for these New Women. When it was mixed with the nearly apocalyptic sentiment for the fin-de-siècle that had lasted for so long as human civilization has existed, though evolved from religiosity to secularity, it is not known how much men would attach sexual desire to the women in Mucha’s posters.

Alone But Not Lonely

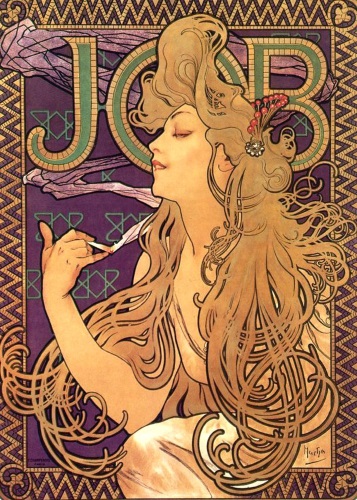

Alphonse Mucha, Poster for “Job” Cigarettes, 1896, Color lithograph, 66.7cm x 46.4cm | Wikimedia Commons

As we can see here, this beautiful woman with swirling Pre-Raphaelite hair, enjoying her cigarette, is clearly indulged in her private world and doesn’t seem to bother making any connections with the viewers. Mucha’s signature Byzantine border and lettering, the use of subdued and pastel-like colors also reinforced the unsurpassable distance between the subject and the viewers, it is almost as if the painter himself was trying to protect his goddesses from being polluted by the modern industrial age. Going back to the distinction between eroticism and sensuality, how then, could audiences be sexually aroused mentally when the feeling of detachment is so obvious? The aloofness of the life-sized figures served almost as a safety cap from the erotic labels being placed onto the subjects, by the viewers.

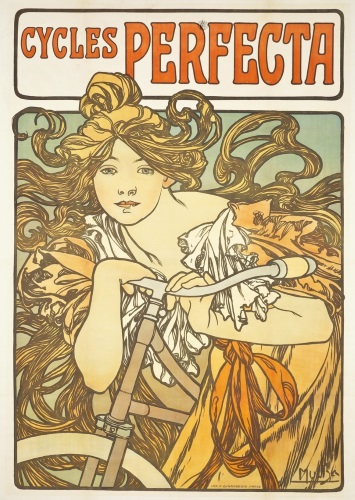

Alphonse Mucha, Poster for “Cycles Perfecta”, 1902, Color lithograph, 53cm x 35cm | Wikimedia Commons

This lack of connection is seen in many other paintings by Mucha. Even when there is direct eye contact, the female figures look as if they’re more drawn to their own mind than the outer world.

Alphonse Mucha, Poster for “Moët & Chandon Crémant Impérial”, 1899, Color lithograph, 60.8cm x 23cm | Wikimedia Commons

Expressiveness Praised

Alphonse Mucha, The Celebration of Svantovit in Rujana: When Gods Are at War, Salvation is in the Art, 1912, Oil on canvas, 610cm x 810cm | City Gallery of Prague, Prague, Czech Republic

All the above debates regarding gender existed in the 19th century because of the liberation of artistic freedom and expressive power. It was a time when ideas like individualism, subjectivity and freedom of expression was high praised, only under such historical backdrop could sensuality flourish and blossom in the fin-de-siècle.

Compared to Slav Epic, the commercial posters Mucha created at the peak of his career might not be the artist’s favorite artworks. They were nonetheless influential to the development of the avant-garde movement and later graphic design. Above all, these posters represented Mucha’s idealistic belief in the purity of art in face of the never-ending turmoil around us, for their sensuality celebrates the improve of modern society while preserves our basic spiritual needs.