Content Advisory: This production contains strobe lights, haze, fog, loud noises, and high-pressure air jets.

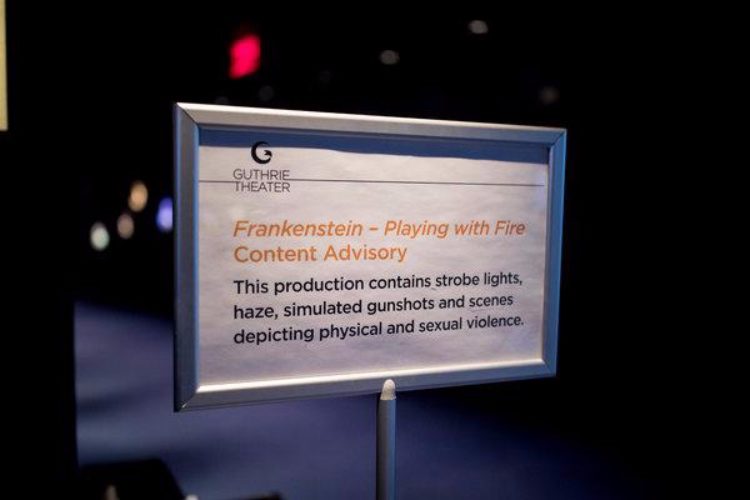

These words were printed in blue font on a sign outside of the Wurtele Thrust Stage as I made my way in to see the Guthrie Theater’s 2018 production of A Christmas Carol. Indeed, a similar sign is posted outside of the entrance to every Guthrie show, part of a systematic effort to inform patrons of potentially triggering material. I’ve seen warnings for profanity, sexual violence, nudity, and more.

Nor is the Guthrie alone – in theaters all across the nation, content warnings are becoming more commonplace, warning against plot points or theatrical events that have the potential to trigger or upset audiences. Strobe effects are typically noted as well, just as in the Guthrie’s production of A Christmas Carol, to prevent epileptic seizures in response to the lighting. Having grown up with them, content warnings signs have never seemed out of the ordinary to me. I walked past them in theater lobbies and could find them online as I ordered my tickets. However, content warnings are still a fairly recent addition to mainstream theater and are still under heavy criticism by some.

And yet, while many still argue that these signs should not exist at all, as they have become more commonplace, many conversations about them have shifted from whether they should exist to what effects they may be having on audiences: accepting their presence, but questioning their use. Susie Medak, the managing director of Berkeley Repertory Theater, argues that by warning audiences beforehand, we are creating a new generation of thinkers that “expect to be protected from discomfort.” She goes on to say, “[t]o me, it’s a frustrating trend — what’s the point of experiencing art if you don’t expect to be surprised?”

Medak’s complaint hits upon the two general themes in arguments made against content warnings: that they breed unchallenged audiences, and that they ruin the element of surprise in the story and the staging. On Medak’s side of the discussion, warnings are perceived as protection from content which, while uncomfortable, holds the potential to expand audience perspectives. Because of them, she argues, audiences have become too comfortable; they remain unchallenged by the theater they choose to see or not to see. As Joseph Haj, the current artistic director of the Guthrie Theater in Minneapolis, says, “As grown-up people, we should be able to grapple with difficult ideas together.” And yet, the Guthrie does post content warnings for each of its shows. Haj explains this decision simply by saying “audiences don’t like to be jumped.”

In the face of A Christmas Carol, though, this argument does not hold up. After all, this show’s warnings are purely elemental – they do not concern the actual content of the performance. Though other times, they warn against sensitive content, that which is either inappropriate for children or triggering to survivors of similar situations. The typical warning says nothing about the politics of the play, arguably one of the most potentially divisive elements within theater today. They are, again, tailored to warn about potentially distressing topics. The distinction this creates, then, between their functional use and the use prescribed from them by their critics, is that content warnings protect against triggering rather than challenging material. James Bundy, the dean of the Yale School of Drama, describes the intent behind these warnings:

“[They are a] genuine consideration given to the unseen and unknown potential for harm when someone is traumatized in ways that could have been avoided.”

So, perhaps it is not that audiences have become too comfortable, but rather that theater makers have become more aware. In posting theater content warnings, we are not discouraging challenging material, but rather discouraging negative theater experiences.

Perhaps there is a way to please both sides of the argument, though. Some theaters, rather than post warning signs outside of theaters, instead allow audiences to request content warnings on an individual basis. The Berkeley Repertory Theater uses a system like this. They encourage patrons to call their box office if they have questions concerning the material in the show. Thereby, the option of the content warning is still available without it needing to affect everyone’s experience.

Although this compromise holds promise for the future, for now, I am perfectly content to continue to see content warnings in the theaters I frequent. The potential harm that they guard against outweighs the loss of surprise in my mind. And besides, just because I know that high-pressure air jets are in the show, does not mean I know when. Sitting inside of the Guthrie Theater that afternoon, they still managed to make me jump.