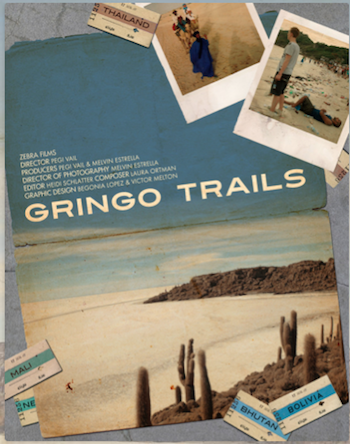

GLOBAL. The documentary Gringo Trails (2013), directed by Pegi Vail, and produced by Pegi Vail and Melvin Estrella, presents the history of globetrotting tourists while turning a critical eye to the impression they leave behind. This is Vail’s first full-length feature, a result of travelling and filming between 1999 and 2009 while pursuing doctoral research on the role of travelers’ stories within globalized tourism. The film is only available to education institutions at the moment, but will engage anyone who has travelled or will travel: budget and thrill seekers, young generations, tour guides and writers, and even host countries with developing tourism.

Gringo Trails encompasses the message of responsible travel. In an era where even the farthest stretches of the globe are accessible to travelers of all ages and budgets, tourism can either support or destroy a community. Vail hopes that local communities gain agency to manage tourism, set standards, and promote education and cultural conservation. “We’ve reached a tipping point based on the sheer number of tourists on the road, and the stakes for locals in what tourism can do for them economically, with many countries entirely relying on the tourism industry,” she said recently in an online discussion.

Gringo Trails opens with a zooming aerial pan of the Bolivian Amazon jungle, densely sprawling with vegetation and gushing rivers. In the back ground, we hear the story of an Israeli backpacker named Yossi Ghinsberg, who was lost for nearly a month in the jungle in 1981, as told by one of his Bolivian rescuers. Following Ghinsberg’s recovery, his memoir Back from Tuchi (1985) incited a surge of backpackers from around the world, seeking similarly harrowing experiences. The Bolivian village, as a result, has irrevocably changed into a jungle town industry; from one hotel to 45, all-inclusive tourist packages and every guide who makes himself part of Ghinsberg’s story, feigning authenticity. This is the gringo trail: tourists who hope to find unique experiences, but actually follow patterns that repeat one another, and sometimes at the sacrifice of remembering their responsibility as visitors to a culture.

The documentary explores cases studies in Bolivia, Thailand, Mali and Bhutan to demonstrate how various stages of tourist development have altered these communities. It addresses issues such as the lack of education for tourists, the “haggling culture” that creates competition among local guides, and the lack of plans for tourist management, which ultimately reorients the north-south development binary. Thailand, for example, seems to serve as a warning of how local livelihoods are entangled in the hedonism of visitors (albeit with mainly innocent intentions), while destroying the integrity of formerly pristine beaches.

Director Pegi Vail, a globetrotting anthropologist and film maker.

Vail is not suggesting that tourists need to quell their travel lust entirely; rather, she suggests that we as travelers acknowledge our privilege and hold greater consideration for the locales. “I definitely still travel! I just don’t romanticize people or places in the same way I did as a younger traveler,” she explains. “You can at least learn as much about the culture you are visiting ahead of time. That costs nothing and will already make you a more responsible tourist.”

The film also transitions between live footage to interviews. There are anecdotes from players in the travel industry at all levels: young backpackers, veteran travelers, National Geographic and The Lonely Planet writers, acclaimed authors like Pico Iyer, policy-makers such as the royal family of Bhutan, and community members who have faced the transformation first-hand. Because Gringo Trails utilizes film and photographs from the early eighties, certain segments lack in resolution, which is also due in part of viewing it on Vimeo. These minor flaws do not distract from the overall message of the film, and that viewers visit beautiful destinations on three continents. Gringo Trails brings a dynamic perspective to the current state of global tourism in under 78 minutes. As a young traveler usually trying to save every penny, the documentary allowed me to reflect upon my experiences and recognize how I can be a better tourist in the future.

A post-party scene on the beaches of Thailand, one of the detriments of global tourism.

So what is the future of backpacker tourism and luxury off-the-grid travelling? Can we realign the gringo trail unto a path of sustainability, consideration and preservation? In the end, Vail believes that grass roots efforts will produce solutions, saying: “The hope was that this film opened the conversation so that we can start working on all these issues, as everyone will have unique approaches! We all need to be at the table and be part of this: from the locals with visions but no resources, to those with resources to work with communities, and so forth.”

Gringo Trails is set for showing in New York City and other film festivals in fall 2014. Be sure to follow Vail on Twitter @gringotrails. For more details on the interview with Vail, visit the discussion thread here.

Correction: May 10, 2014. An earlier version of this article erroneously stated that the film is directed by Pegi Vail and Melvin Estrella. It is directed by Pegi Vail, and produced by Pegi Vail and Melvin Estrella.