Read this article in Spanish here.

In reporting stories attached to radicalism and extremism, the media has a huge responsibility to provide understandable information on groups of people or actions defined as ‘radical’ or ‘terrorist’. Not only must journalists and news firms publish facts highlighting and enforcing the devastating consequences of radical or extremist behavior, they must also ensure that these words are not misused. Whilst free expression in a democratic society allows anyone to spread their views without fear or reprobation, there is an appropriate treatment of these topics that must be upheld. ROOSTERGNN spoke with Erin Saltman, a Senior Researcher at Quilliam Foundation and an expert on Political Socialisation, about the responsibilities of the media in this context.

In your report on Jihad Trending, you say that fighting extremism is the duty of all responsible members of society. What advice do you have for new journalists or future journalists as to how to continue to fight this extremism?

We do feel that everyone has a role to play, not least the media and journalism. One of the findings of our report was that sometimes when people are introduced to extremist trends or terminologies through offline communication, one of those being the media, there is certain typecasting, stereotyping and language used when talking about Islamic extremism that isn’t necessarily used for other types of extremism.

For example, in the Brevit case in Norway, before the suspect’s identity was known, all the headlines would say ‘Terrorist’ or ‘Norway’s 9/11’ and hypotheses about Al-Qaeda’s involvement, and the words ‘Terrorism’ and ‘Terrorist’ came up a lot. Yet as soon as it was found out that it was a non-Muslim white person who carried out the attack, all the headlines said ‘Lone Gunman’ instead of ‘Terrorist’.

This is problematic, because even in focus groups that we held with young Muslims, the participants said that the words ‘Terrorist’ and ‘extremist’ made them think of Muslims.

This is not what the media should encourage and I think it is imperative that we take more care with terminologies and be better at conveying the histories of certain groups. The media should express why certain trends should not be followed and why we are condemning a group – not just define them as bad.

What is your opinion on the “Right to be Forgotten” legislation in a freedom of expression context?

I don’t necessarily agree with the ‘Right to be Forgotten’ because it builds a curated history. Previously, we know that history has often been written by the winners and one of the liberties of living in a digital era is that history can be written by anyone who has a voice and wants to relay their story.

When we start being able to select what can be found online, and indeed our own histories, then you can already imagine what some trends will be. If you go on the websites that allow you to ‘click to be forgotten’, it asks whether you are the individual or the person’s lawyer. You can see some biases, since, if someone wants to be forgotten and can afford a lawyer; they will have stronger cases than perhaps the average individual.

So, we don’t believe in curating history and nowadays the types of things that the ‘Right to be Forgotten’ is mostly concerned about are images on Facebook that you wouldn’t want to get out or things from your past. We now have digital literacy so we’re already able to create settings allowing or preventing the public from viewing delicate material, so really we shouldn’t be punishing private companies for our own flippancy when we make something available then regret it later.

What changes would you like to see in our society in fighting radicalism?

First and foremost, we would like to see the offline efforts combating radicalism reflected more truly online as well, because there are some amazing offline efforts in local community groups fighting certain extremist trends and that is not often found online, so sometimes it goes unnoticed. We would also like to see the fight against radicalism mimic other fights that we have seen to be successful. We already see a higher level of intolerance towards discrimination such as homophobia, sexism or racism, which we currently don’t see in the fight against radicalism. If we could campaign and get more people active about challenging extremist and radical narratives in the way that people feel comfortable challenging homophobia, sexism and racism, that would be very beneficial.

What do you see as the line between radicalism and the freedom of expression?

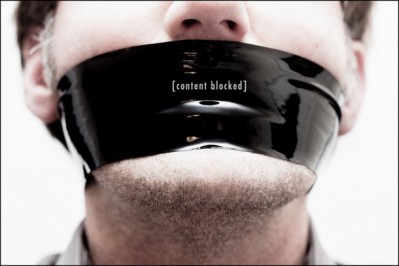

It is legal to have a somewhat extremist opinion and ideology. We live in a democracy, and therefore we cannot decide which ideologies are acceptable and unacceptable. Freedom of Expression is regulated by clear and concise laws which define what is illegal – for example incitement and calls to violence, hate speech or support of terrorist organisations. There are clear definitions around what terrorism is and what terrorist or hate speech guidelines are, but if extremism in general is not breaking the law, it is freedom of expression and therefore should not be censored or blocked.

In a religious context do you think that the ideology of terrorist groups is a part of the necessary information of the story and therefore should be mentioned in the media? In other words, Should journalists give special treatment to news regarding religion or should such news be treated just like any other information?

It is a bit of a grey area I suppose. Extremist and terrorist organisations tend to interpret and misconstrue religious narratives as a way of giving legitimacy and credibility to their violence. The vast majority of Muslims or religious people in general do not hold these values. The problem is that a very active and vocal minority that is espousing these twisted ideologies is falsely representing the somewhat silent majority. As far as the media is concerned, this should be exposed. It does not always come across that these are the views of the minority, thus people of America and Western Europe often get a misperception of Islam because everything we hear is a negative and typecast view made from a twisted form of an ideology.

What are some of the tactics you use in teaching women, like the Muslim Outreach Programme, in order to combat extremism?

We do various forms of Outreach; one of the things we would like to continue is teaching people not to be afraid to be active and vocal online – not just with women but with anyone in a community who wants to create a healthier marketplace of ideas.

Our Outreach work is also trying to re-empower communities. I think that especially within the UK, but also perhaps within France and other European nations, you see that the Muslim communities are quite silent around certain topics and quite fearful to be vocal and active because of treatment that they have had in the past, or a feeling of disempowerment as a community. We aim to counter this negativity and recreate a positive activism.