Immigration is a typical example of a global phenomenon which can’t be tackled efficiently by singular States, and exemplifies the convenience to operate in a common political arena such as the European Union.

Since the creation of National States and the definition of their borders, the definition of the “citizens” as the individual benefiting from the rights accorded by his State, involved on the other land the definition of the “outlander” as the individual missing rights because of lack of relationship with the State in question.

Following the institution of the Schengen area, the distinction between “citizens” and “non-citizens” became a distinction between “European and “non-European”, and the monitoring of the external borders of the European Union have become so intensive, that our continent has been called “Fortress Europe”.

Why immigration is perceived as a problem?

Today we assist to the same social reaction, towards the phenomenon of immigration, which have always occurred throughout history during the periods of economic downturn. With several countries in Europe governed by right parties, and the rising of far-right political parties in the recent years, a widespread fear and wariness can be observed in many European countries. In the countries in which economic resources are still shrinking, the repartition of wealth becomes a serious concern for their inhabitants, and immigrants are perceived as the illegitimate usurpers of the remaining resources. Useless to say, fear and basic natural instinct have always been exploited by political players to find new supporters.

Other than the argument about the repartition of wealth, immigration raises also new concerns regarding security measures. And here it is why a European common action is indeed so important: the problem of identification of the people arriving in our countries. People is wary towards immigrants and States are wary towards the other Member States, many of which have lately suspended the implementation of the Dublin Agreements, omitting to register the immigrants passing through their territory to not be obliged to host them in their countries.

What the Member States are doing?

Frontex and national police forces have already started cooperation through the Europol agency, in order to identify economic immigrants (which can be considered illegal according to the actual legislation), and refugees, benefiting on the contrary of international protection.

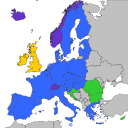

New weak initiatives just come to be taken. During the meeting of the Head of States and Government held on the 23rd September, the European Council approved with the majority of the votes (the unanimity hasn’t been reached) to relocate 120.000 migrants within the Member States. Although Romania, Hungary, Czech Republic and Slovakia had rejected the proposal, they are now forced to comply with the regime of quotas proportional to the countries’ population. Their opposition is reasonable if we think that former-communist countries have been isolated for roughly 40 years, and phenomena such as xenophobia and discrimination are rather widespread among the population.

Starting from November hotspots will be working in the Southern-European countries: they will be centers where Frontex, Europol, the European Asylum Support Office (EASO) and national police forces will cooperate to identify immigrants. The Member States have also started to debate about the institution of a Common Asylum System, a proposal originally advances by the Italian government during the semester of its Presidency of the Council of the European Union (July – December 2014).

Following Triton, it seems that the European countries are gradually taking the commitment of sharing the burden of immigration. The provisions of the Dublin agreements have been unilaterally suspended in many countries (Germany, Hungary and Austria have arrested rails transports between the countries) and Germany stated it will host refugees even in case they have been registered in another European country.

Among negotiations and unilateral decisions, it seems that European countries are moving forward regarding the immigration policy. After all, the emergency urges a solution: according to the Association for Juridical Studies on Immigration (ASGI) the rate of rejection of asylum application is profoundly divergent among the European countries, due to highly distant legislations. As a consequence the same request can end up with a different result, depending on the country where it has been presented. A harmonization of European national legislations is then necessary: rather than contrasting illegal immigration, Europe seems starting to understand that, by providing a safer way to enter Europe, the illegal debarkation of migrants and human trafficking would be reduced.