On December 17th, Natale ai Caraibi, the latest Cinepanettone, as italian Christmas movies are named, will be across cinemas (you can find out more here).

But what is a cinepanettone (a neologism in which “cine” comes from “cinema”, and panettone is a kind of sweet bread traditionally eaten at Christmas) ? Any Italian would define it as popular blend of vulgar jokes, stereotypical characters, sassy showgirls and exotic locations, which every year displays and celebrates the latest italian fads and obsessions. By contrast, according Alan O’Leary, professor at University of Leeds, 3 simpler traits seem to be the most important: the cinepanettone is part of a ritual; it is watched by many Italians; and it is despised by many others.

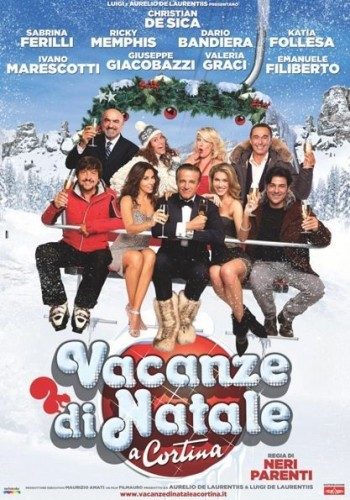

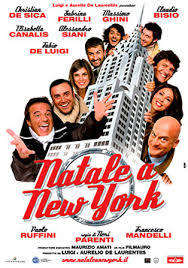

In his examination of this research strand, O’Leary delimits the field by including only the films starring Christian De Sica and/or Massimo Boldi. These farcical comedies, which were born in 1983, invariably display middle class members having holidays in fancy locations such as India (Natale in India, 2003), Egypt (Natale sul Nilo, 2002), Usa (Christmas in New York, 2006, or Christmas in Miami, 2005), Cortina d’Ampezzo (Vacanze di Natale a Cortina, 2011) or the Netherlands (Merry Christmas, 2001). Directors included Carlo Vanzina, Enrico Oldoini, and Neri Parenti.

Altough moviecritics are generally very dismissive of this genre, some of them believe their bad taste and disrespect for/ objectification of women to be shaped on Berlusconi’s broadcasts. O’Leary makes a distinction between movies shot in the 90es (especially those by the Vanzina brothers) which have references to Italian society, and the more recent ones which do not. If this happens because of political reasons (i.e. Berlusconi’s decline) or business reasons only, it is nor clear, although as Marco Martani (one of the writers) recalls:

“The goal of the Christmas film is to make people laugh and to make as much money as possible. Period. If it reaches these two goals, then the film is a masterpiece”.

A fundamental reason for the enduring success of these lighthearted movies is distribution. The cinepanettone is distributed in about 850 prints, rivalled occasionally and only by Hollywood productions. This means that, if a spectator, performing a ritual, goes to the cinema, it is quite likely that he will find a cinepanettone screened in the theatre he chooses to attend.

Another reason for its success, as said above, is that going to see a cinepanettone, no matter how sexist, or trivial it is, has already become a Christmas tradition. As scholar Guido Simoncelli notes, any representation of actual festivity have disappeared from the Italian Chistmas movie. There is no Christmas tree, no presents, no midnight mass. As O’Leary highlights,

“the films themselves don’t have to show the religious and familiar celebrations, because they are already themselves part of the celebrations”.

What is peculiar of Christmas for you? Let us know by tweeting @ RoosterGNN or @bluelisaaa using the hashtag #cinepanettone.