Supply and demand, vendors and consumers, capital and labour: these are the pillars of the free market economy capitalism is based on. Capitalism in its simplest form has been around since the middle ages, in the form of lending money at interest – then considered the sin of usury. Ever since the rise of trade in 13th century Europe, it has been explored by economists such as Adam Smith, David Ricardo, and Jeremy Bentham.

However, not even history’s greatest philosophers could predict today’s technological revolution that is changing free markets forever. With services online becoming available at very low costs, our economy is experiencing a paradox. The first instance of this was seen with Napster, the first platform to distribute music for free, in 1999. This shook the music industry, leading to lawsuits such as Metallica vs. Napster and discussions of intellectual property. Surely, distributing music without paying the artists could never work? But despite Napster’s ultimate failure, the number of online file sharing not-for-profit platforms has only increased: YouTube, Spotify, Soundcloud, among others.

The same started happening for the newspaper, photography, and publishing industries, with consumers sharing information and services online and ignoring typical market rules. This zero-marginal-cost economy has changed the face of business, with vendors actually doing better overall when providing cheap or free-of-charge services. Take the music industry as an example; the easy digital distribution of files is largely to blame for the record business’ decline. However, the combined value of other sectors of the industry (live performances, recordings, etc.) rose from $51 billion in 1998 to over $71 billion in 2010.

Music, like other industries now based on free content distribution, has economic relevance beyond the number of physical copies sold. It is defying the usual cycle of supply and demand and thriving on a system where money comes from other sources – ads sold on online listening pages, fans buying digital copies of an album after having already heard its content on YouTube, for example. What is most important for artists, writers, and other professionals nowadays isn’t being directly rewarded for their creative labour; it is sharing their content with a wide audience to gain popularity and build a follower base from which they will then reap benefits. According to Mat Callahan:

Musicians are discovering that the only real protection or incentive they can hope to gain is from their audiences, those people who need what they do and will support them doing it. And audiences are people, not markets. This is why the greatest rewards are not quantifiable in monetary terms, nor can they be taken away by unscrupulous business people unless they are willingly surrendered.

This marginal cost reduction is beginning to change other industries which should also be subject to regular forces of a capitalist market. People are making products for their own use through 3-D printers; those switching to “green” energy sources, despite paying an initial hefty sum, will power their own households, share surplus energy with neighbours, and manage their own electricity. Car sharing services are becoming increasingly popular, with 1.7 million users worldwide and members preferring access over single ownership. “This collaborative rather than capitalistic approach is about shared access rather than private ownership”.

This new system is not entirely positive. Blockbuster had 9,000 stores in the U.S. with a total of 83,000 employees, while Netflix only employs 2,000. However, the labour market is gradually being taken over by machines – automated transportation , factories, online retailing, and more are cutting down employment opportunities worldwide. Workers, once valued based on how much better they could perform a job than their neighbour, can now easily be replaced by technology. Their worth in the market has become based on their creativity – their ability to solve problems in a novel way or confront issues that have not yet been considered. A clear example is the creation of eBay or Amazon: a desire to purchase goods without leaving the home has changed the way we think about retail.

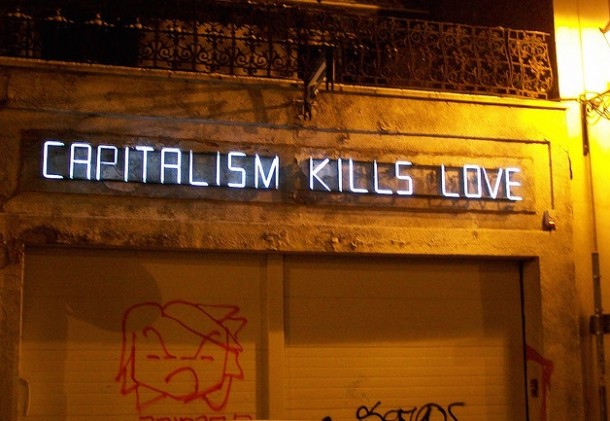

The change in attitudes toward capitalism is reflected in the political stances of Millennials, the demographic most in support of the rise of today’s “New Left”. The U.K.’s Labour party has shifted towards extremes under new leader Jeremy Corbyn; Spain’s Podemos is gaining popularity and predicted to make significant gains in December’s elections; anti-austerity Syriza has won two successive elections in Greece. In the U.S., self-proclaimed socialist Bernie Sanders is a serious contender in the 2016 presidential race. Even the Pope is warning against the “invisible tyranny of the market” and calling for a return to an economy more focused on human beings.

Is this political shift a rejection of capitalism in its current state – under the monopoly of “big businesses” and corporations? If the popularity of the Occupy movement started in 2011 is anything to go by, what people want is not necessarily a socialist utopia but a reformed, fair, and truly free market system. No more crony capitalism; no more “Dictatorship of Big Corporations”. With the burgeoning of virtual markets and a technological revolution, the way our wealth functions is bound to change. This, combined with popular discontent with the status quo, are not threatening the existence of capitalism – it will likely remain our service trading system of choice for a long time – but forcing it to adopt a new, more efficient role in our economy. “We are entering a world partly beyond markets, where we are learning who to live together in an increasingly interdependent, collaborative, global commons”.