Ethiopia´s northeastern regions of Tigray and Afar are facing the country´s worst drought in over 50 years, expected to be even more dangerous than the one in 1984, which led to a famine that took more than 1 million lives. In this case 10 million people are in danger of starvation, 5.8 million of whom are children.

This is one of the many issues that are going to be discussed at the 2016 AIDF Africa Summit on Monday February 2nd, an aid and international development forum held in the Ethiopian capital this year. Experts hope that the event will attract some media attention, which has been lacking since the first signs of the mega drought were spotted in June 2015.

The United Nations and Save the Children have both announced that the crisis is not being taken seriously enough by the international community, whose attention seems to be focused on the political turmoil happening in the Middle East.

In December of last year, the Ethiopian government appealed for 1.3 billion euros in foreign aid, but authorities claim that only 180 million dollars has been received so far. The harsh economic reality is that Ethiopia is competing for international funds against war-torn Middle Eastern regions such as Syria and Yemen, and with the resources that European states are allocating to the accommodation of thousands of migrants.

Mitiku Kassa, the commissioner in charge of Ethiopia’s Disaster Risk Management and Food Security Agency, confessed that “They [the donors] probably assume that the magnitude of the hunger problem in Ethiopia is less serious”. But both Save the Children and the UN World Food Program (WFP) warn that the crisis could have effects of almost unprecedented magnitude. Carolyn Miles, chief executive of Save the Children US told the press that:

We only have two emergencies in the world that we have categorised as category one. Syria is one and Ethiopia is the second.

But how could we get there once again? A little over 30 years ago the world came to rescue Ethiopia from its last tragic drought, but many were under the assumption that the country was going to put a system in place that could avoid this type of emergency situations.

Ethiopian leaders have been accused on numerous occasions of misspending the humanitarian aid received for political favors. But in the last 30 years the country has actually started several programs to tackle the issue, such as a national food reserve, the Productive Safety Net Program – an initiative that pays work for infrastructural and public service projects with food – and even a railway line to facilitate distribution.

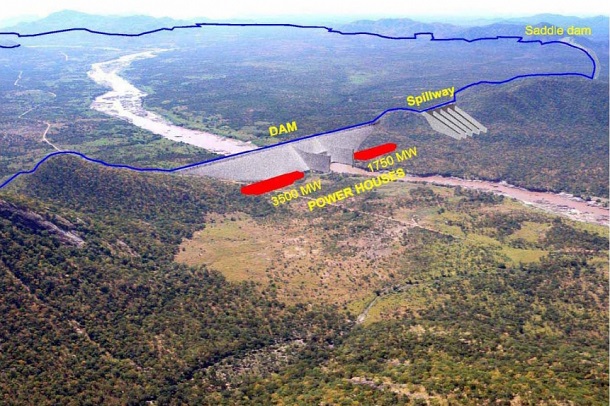

This has launched the country into a period of relative economic prosperity and made it one of the fastest growing economies in the world. Although the primary source of income of the great majority of the population – about 80% – is still rain-dependent agriculture, the cities are rapidly modernizing and the government is investing on infrastructure to support this economic boom. The most important project is the 5 billion dollars Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam, Africa’s biggest, which is being built to generate enough hydro-electricity to guarantee the country’s economic security.

The UN´s commitment to humanitarian relief in the Middle East makes private contributions to NGOs working on the ground one of the few possible solutions to the problem. The need for international funds isn’t just to save lives but to ensure that Ethiopia keeps its current developmental momentum – and with it its best chance of being able to handle such droughts in the future – and avoids a catastrophe that would have a ripple effect through multiple generations.

If emergency funding doesn’t escalate very soon, there is a real risk of reversing some key development progress made in Ethiopia over the past two decades, including the reduction of child mortality rates by two thirds, and halving the percentage of the population living below the poverty line

John Graham, director of Save the Children UK, said.

According to environmentalists, the drought might be linked to extreme weather patterns due to global warming that are going to manifest with increased frequency in the next years. Warm temperatures will make food and water less accessible, endangering large parts of the world´s poorest populations.

Geir Olav Lisle, Deputy Secretary General of the Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC) warns the international community against donor fatigue, a potential threat to international emergencies after a 2015 riddled with so many humanitarian crisis.

We cannot risk that the drought in Ethiopia is overshadowed by the Syria crisis and other ongoing emergencies.