In the last few years, the world has seen the movement of millions of people towards Europe to escape war, poverty or political oppression in their own countries, largely because of the biggest refugee crisis since the World War Two. This has reignited the long-standing immigration debate in most countries throughout Europe, with David Cameron, Former Prime Minister of Great Britain, describing migrants in Calais as “a swarm” in June 2015.

BBC/ ONS

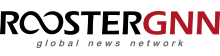

The UK has seen much lower levels of asylum seekers being granted reaching the UK; this is largely down to the fact that it’s much more difficult to reach the UK, an island with borders in France, than Germany or Sweden. Additionally, due to the Dublin Regulation, asylum seekers must apply for asylum in the first country in which they arrive, and if they continue on their journey after doing so, can be deported back where they were initially processed.

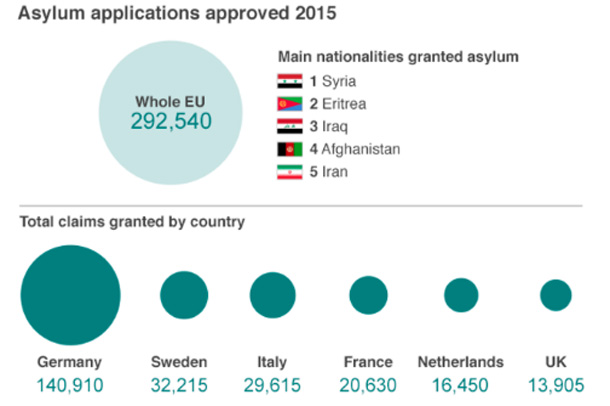

However, with the increase of immigration including EU migrants coming to the UK in 2015, net immigration has continued to rise and it has been become a serious topic of debate in British politics. This has lead to a rise in right-wing anti-immigration parties such as the UK Independence Party (UKIP) that got 12.6% of the national vote in the 2015 general election, an increase of 9.5 percentage points from the 2010 election. At the same time, 2015 saw a peak in international migration to the UK at 330,000.

BBC / ONS

The issue is that these groups; asylum seekers, refugees and economic migrants are often spoken about as one; as though refugees, asylum seekers and economic migrants are all the same. As defined by migrantwatchuk.org, an asylum seeker is;

“A person who has applied for asylum under the 1951 Refugee Convention on the Status of Refugees on the ground that if he is returned to his country of origin he has a well-founded fear of persecution on account of race, religion, nationality, political belief or membership of a particular social group.”

A refugee is someone that has been successful with their “asylum seeker” application. In the broader context, it is someone that may be fleeing civil war or natural disasters, but not necessarily fearing personal persecution should they return to their home country.

An economic migrant is someone that leaves their country to find work. Sometimes economic migrants apply for asylum as a means of legitimately getting into a country, but as they are often able to return to their country without persecution, they aren’t granted refugee status and are detained, deported or both. These three terms are often conflated by the media, making the debate around immigration even more difficult to have.

Nigel Farage, prominent British right-wing politician poses next to controversial Brexit poster | The Guardian

The difference is important in order to be able to discuss immigration properly, in order to avoid scaremongering like the poster used by UKIP and its leader, Nigel Farage as part of the Leave supporters during the Brexit campaign. The people seen in the poster above were refugees, crossing the Slovenia border with Croatia, with no evidence to suggest any had arrived in the UK.

As we’ve seen in the last few years, the reasons for migrating are often different. Some flee war, some poverty and some are trying to find a better life. Some former interpreters from Afghanistan sought asylum in the UK, whose soldiers they helped in the war. They now flee their country in fear of reprisals for helping British soldiers. They weren’t granted asylum.

The challenges governments face are offering asylum to those who need it most (which is their international obligation) while keeping immigration levels low at a time when immigration is not popular among the electorate.

Lampedusa, Greece, 2007 | Sara Prestianni

Economic migrants may not be fleeing war-torn countries, but they aren’t necessarily better off than asylum seekers or refugees. The Global North has long reaped the rewards of its more powerful position over the Global South and has often exploited that relationship. The inequality this has now created acts like a magnet, pulling migrants towards rich, Western countries. Just as migrant workers come from Africa to Europe, so do Central Americans (especially Mexicans) to the USA. The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) has, contrary to its goals, worsened inequality between the US and Mexico.