If you are tired of mojitos and fed up with daquiris, there is another Cuban drink that is just as sweet and refreshing, with a history as rich as its flavour. Entering the colourful bars and cafés of the Spanish colonial city of Trinidad you will soon notice an intoxicatingly energising cocktail on the drinks list that, after having a few, will allow you to exercise the Spanish skills you never knew you had. The canchánchara, pronounced exactly how it is spelt, is a simple yet powerful tipple made up of five main ingredients: honey, lemon, aguardiente rum, ice and water, to be added in that order.

One of the best places to go for the cocktail | Gina Agnew

When asking where to find the canchánchara you will be spoiled for choice by a number of eager bartenders claiming theirs is the best. Of course, the owner of the eponymous bar La Canchánchara would argue that his establishment was where the drink first surged to popularity, whereas the bartenders at the high-end Vista Gourmet say that they perfected the recipe behind their bar. However, of the dozen cancháncharas sampled in Trinidad, I found that the best was made in the modest comfort of a friend’s home.

Julio making a professional canchánchara | Gina Agnew

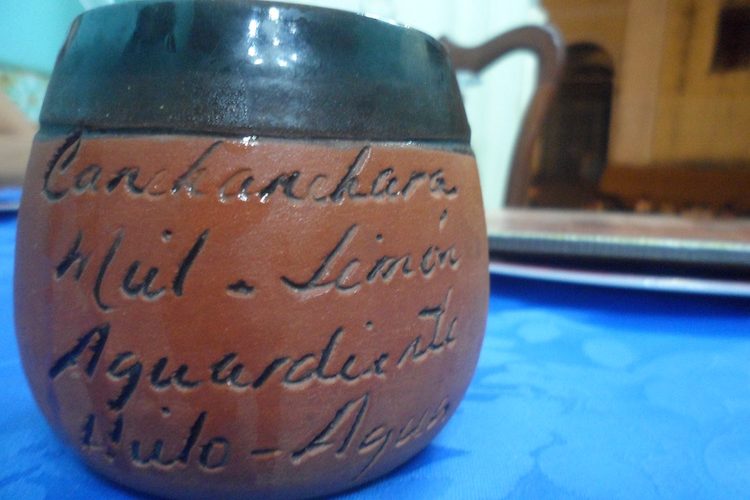

While whipping up a batch, Julio Rodriguez, a 24-year-old mechanical engineer and seasoned canchánchara maker, explains how “the mixture of ingredients represents the mixture of Cuban cultures.” It is traditionally served in a copa de barro, a small clay mug created by the indigenous Cubans. Modelled on the fruit of the gúira tree, this cricket-ball sized cup holds the perfect quantity of ingredients to make up the best-tasting canchánchara. Often, these ingredients are delicately engraved on the side of the mug, resulting in both an authentic souvenir and crafty reminder of the essential order of contents.

Recently proving itself as one of the definitive attractions of Trinidad, tourists have been bar-hopping to discover where the best canchánchara is made. Mohammed Tasadiq Khan, a 30-year-old quantity surveyor from Yorkshire, admits the importance of the mug to the flavour of the drink. “I’ve tried them from a plastic cup outside on the Parque Cespedes street parties and the quantities were all wrong. The honey was too thick and there was too much rum. You need the little mug to measure it out correctly,” he shares. He later added, “I don’t think I could drink it anywhere else without being reminded of Trinidad, it has a very distinct taste.”

The Valle de los Ingenios with sugar cane plants | Gina Agnew

A mixture of cultures define its main components, and originally served as a hot drink to remedy illnesses triggered by the morning dew and hard labour, canchánchara’s ingredients hold both medicinal and invigorating properties. First comes the honey that lines the bottom of the mug. Cuban bees, unlike their international counterparts, are in significantly less danger of extinction given the lack of pesticides used on the plants they pollinate. Much of the honey used in Canchánchara, then, is purer and glistens brightly in a hue of Trinidad yellow since it is the mango flower from which the pollen is gathered. Then follows the lemon juice, freshly squeezed and strained to avoid a lumpy consistency when mixed with the viscous honey.

Sugar cane picked and ready to make into rum | Gina Agnew

Next comes the once slave-produced rum, aguardiente, which is obtained by the fermentation and distillation of sugar cane, and is charateristic of this region of Sancti Espíritus. Alexis Torres, owner of the restaurant and bar Siboney in central Trinidad, shares the religious connotations of the rum. As he poured a few drops into his hands he explained how the first few sips must be offered to the Cuban spirits before anyone is to drink it, out of tradition and respect. The name, aguardiente, can be interpreted as “fiery water” given its harsh, abrasive taste; another reason why the addition of honey is so essential to the recipe. The historical significance of this type of rum dates back to the 18th century when, after driving the indigenous population to near-extinction, the Spaniards brought over legions of African slaves to work on the sugar plantations under an exploitative regime of forced labour. The poetry of conquistador Don Carlos Manuel de los Cespedes only becomes more ironic through his line, “Yo brindo a la libertad con aguardiente de la cana,” (I toast freedom with the aguardiente of the sugar cane).” Today, in Valle de los Ingenios, a 15-minute drive from Trinidad, many of the sugar cane plants have been replaced with mango trees, but the Afro-Cuban traces of the canchánchara’s flavour live on through the rum.

It goes without saying that this cocktail is a mouthful both in flavour and pronunciation, but however you experience the canchánchara, you are drinking in a vital element of Cuban national history.

To sample the best cancháncharas:

Vista Gourmet

Callejón de Galdós y callejón de Gallegos

(+53) 41 99 67 00

Opening hours : Daily Noon- 11p.m.

La Canchánchara

Rubén Martínez Villena e/ Piro Guinart y Ciro Redondo

Telephone: (+53) 41 99 62 31

Opening hours: Daily 9a.m.-9p.m.

Siboney

José Martí (Jesús María) e/ Camilo Cienfuegos (Santo Domingo) y Lino Pérez (San Proscopio)

Telephone: (+53) 52 83 82 48

Opening hours: Daily 10a.m.- 10p.m