The concept of petitions has been around since before the 18th century, while the formalization of petitions as we understand them, used for legal purposes, evolved as a form of protest becoming common in the United Kingdom around the 18th and 19th centuries. And today, the Petition Clause of the First Amendment to the United States Constitution serves as the guarantee of the people to air their grievances to the government, included in the clause is the right to file lawsuits against the government itself. Suffice to say, petitions hold an incredible amount of power.

However, with the evolution of the internet came the evolution of protest and activism. Online petitions have inundated social media, including those handled by private organizations and government-based petitions alike. Signing a petition has become so easy that one can sign over a dozen in less than a minute on Change.org, a petition website operated by for-profit Change.org Inc. This is a company that claims to have over 240 million users throughout the world. Signing one’s signature on a petition has never been so easy.

Moreover, governments throughout the world have adapted to take advantage of the ease that online petitions offer, with e-government petitions offered to citizens. These include the UK Parliament petitions website, the We the People platform created by the U.S. government for signing petitions on the White House server, and even the European Parliament Committee on Petitions that has offered the right to petition within the union, using a web portal to create and submit petitions.

Certainly, the use of online petitions lessens the effort once required to sign one’s name on a petition, even if that just means getting out of one’s house. And for the less fortunate, marginalized, and minority groups, the existence of online petitions provides a means for their voices to be heard. And as much as that is true, the momentum and results of online petitions reveal certain dilemmas that begs for a more thorough understanding of their efficiency, effects on human behaviour, and overall worth.

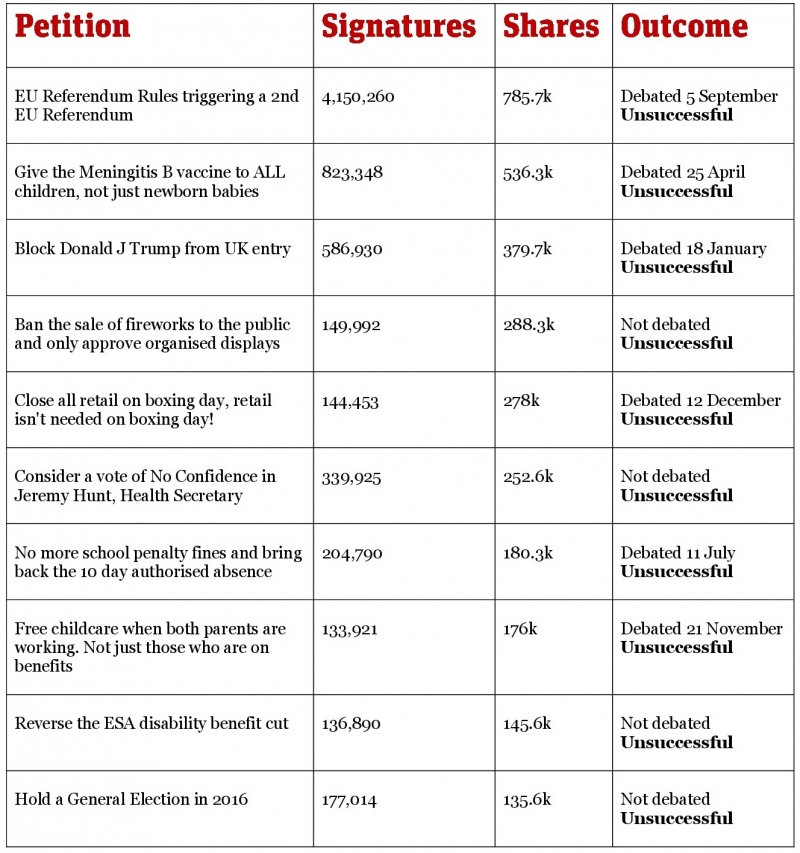

Utilizing the BuzzSumo analysis tool, here are the top ten most-shared campaigns from the UK Parliament petitions website:

Most Shared Campaigns from the UK Parliament | BuzzSumo

Despite accumulating millions of signatures and hundreds of thousands of shares, none of these campaigns succeeded in attaining their intended result. The numerous critics of “slactivism,” the pejorative term for “feel-good” measures taken in support of an issue or social cause, might not be too surprised by these damning results. The claim is that the ease of online activism now provides the same shot of dopamine that often accompanies doing something one believes in – in support of a cause bigger than one’s self.

Even so, the fact remains that petitions signed by millions of signatures sends a remarkably potent message. The petitions above, to a great degree, represent the will of the British people; it very much resembles the foundation upon which democracy is built – to listen and adhere to the will of the people, governments are beholden to their citizens. In 2017, a million Brits petitioned the UK government to hinder Trump from meeting her majesty, the Queen, before being rejected by the UK government. Imagine the extra security protocols needed for that visit, with the awareness that protesters would bombard the American president.

Trump protest | Pixabay

Despite the seemingly-abysmal picture painted by government petitions, Change.org reveals a slightly more promising picture. The world’s largest e-petitioning website boasts a victory page that is truly inspiring. It has triumphantly aided the fight to end taxes on tampons and all sanitary products for women within the EU, when the parliament accepted a tampon-tax-ending amendment in 2016, two years since the petition appeared on Change.org. And in 2012, the 15-year old Malala Yousafzai, who was shot in the head by a Taliban gunman, was petitioned to be elected to win the prestigious Nobel Peace Prize. Malala was nominated for the prize in 2013 and awarded the prize the following year.

Success stories such as these serve to demonstrate the reality that petitions can truly inspire real change. But it pays to be wary; it is worth mentioning that in 2016 there were only four petitions in the UK that Change.org considered significant enough triumphs to have warranted a place on their “Featured” page. At this very moment, according to Change.org, there are 263,834,712 people taking action. How many of these will be successful enough to become featured on their home page?

However, in the end, the answer is not to stop lending one’s signature to the next issue or cause that calls to one’s attention. After all, there is nothing to lose from signing something you agree with and believe in; one cannot adequately predict which appeal may defeat the odds and bring about lasting change. Instead, one should refrain from falling into the trap of passively protesting online; from simply clicking one check box after the other, by matching your online protests with similar offline action. Now, there are multiple petitions on Change.org to include climate change in school curriculums. Picture a generation that grows up understanding the responsibility of humankind towards the environment. Imagine that those children were the adults of today’s society: the CEOs, prime ministers, and presidents of the world. Perhaps there would be no climate change to fight.

Greatly assuming that this generation does enough to salvage the earth for numerous future generations, would not having the children of today grow up with the awareness of sustainability’s value be a wonderful – dare I say worthy enough – cause to match one’s online protests with equally effective offline demonstrations?.. despite the extra effort.