U.S.A. Janeen Smith is turning 25 years old this year, a number that sends chills through her spine. “I owe twice as much with a few zeroes added to it.” She refers to $50,000.

Smith graduated from the University of Maryland in 2009, majoring in political science. Since then, she has held odd jobs here and there, earning $7 per hour. Her dream of pursuing a law degree has had to be scrapped; adding to what she owes simply cannot be justified. Luckily, her parents enjoy her company.

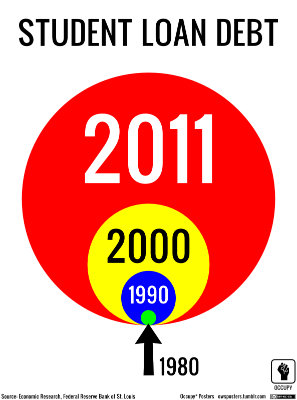

Sadly, she is only one of the thousands of jobless graduates, living with their parents and indebted to the brim. According to an article in The Christian Science Monitor, “cumulative student loan debt now tops $1 trillion, more than American consumers owe on credit cards.” The same article profiles four further students with student debt ranging from $35,000 to $191,000.

Yet the above featured individuals are the lucky ones. There is another group that could not make it as far: the dropouts. A December 2009 research study conducted by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation surveyed more than 600 young adults and found that those who had dropped out did so “not because they’re lazy or uninterested in higher learning—it’s because they need money for survival.” There is a striking difference between the dropouts and the graduates: 70% of the former received no financial assistance, while 60% of the latter did.

But for those who leave school, the financial nightmare doesn’t end that very day. Most of them walked away with an average debt of $8,200 of which the first payment was due within 25 days of receipt. The timeframe for repayment will differ depending on the loan agreement. Some lending institutions provide students who drop out of school the same six month grace period before requiring repayment, although many don’t allow more than 21 days. However, some institutions require that payments be made immediately after the student drops out of school. While a school may inform the lending institution that the student has left school, the student should also provide this information to avoid being held delinquent in her payments. For these individuals, the future is also grim, perhaps grimmest: no degree, little chances for a job, -let alone a well-paid one,- pressing financial constraints and a debt that is now due.

“For as long as I’ve been alive, Congress has always agreed to pay for and fund senseless, needless wars,” says Smith. “When it comes to education however, the deficit is too high; cuts must be made,” she says, anger and frustration filling her eyes.

According to the National Priorities Project, the running and accumulated total cost of war for Iraq and Afghanistan, from 2001 to present, is $1.5 trillion. To put this figure in perspective: if that much cash were distributed among the current U.S. population, every single individual in the country would receive $4,800.00. (Recall that the running total is only for two of the wars US has waged over the past decade.)

By contrast, a measly $50.9 billion was set aside for college education in 2010, $44 billion in 2005, $22.4 billion in 1990, according to the National Center for Education Statistics. To put it in perspective, if a 10-year average education funding amount, approximately $391 billion, were distributed, every single individual in the country would receive $1,251.00, that’s four times less than the cost of just two wars in the past ten years.

Clearly, the elected officials do not see education as a priority. And so, the institutions that once illuminated the path for students from world over are slowly, gradually dimming out behind a thick cloud of steadily decreasing educated men and women who are still carrying the pride of belonging to a country that was once the envy of the world.

If children are the future and education is the key to progress, it’s time to implement drastic changes to fund education without reserve, as if our lives depend on it. Because our future, our lives do indeed depend on it.