TUNISIA. On Wednesday, March 18th, more than twenty civilians were killed in a shooting attack at the Bardo Museum. The French Foreign Minister Laurent Fabius tweeted “Attack in #Tunisia: Today #terrorism has struck—and this is not by chance—a country that represents hope in the Arab world.” Is there such a hope? Tunisia has struggled with violence perpetrated by Islamic extremists since mass protests ousted President Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali in 2011. The Islamic State and other extremist groups immediately claimed responsibility for the attack.

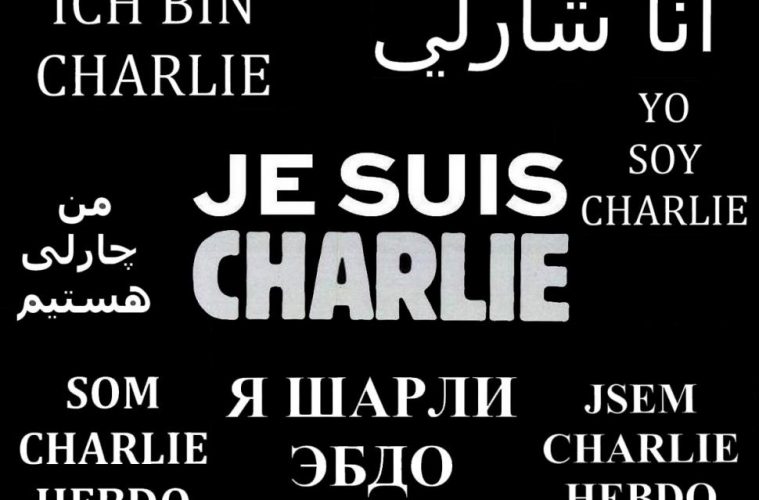

Only two months have passed since January 7th, 2015, when Chérif and Saïd Kouachi forced their way into the Paris headquarters of the satirical weekly newspaper Charlie Hebdo and opened fire against its editorial staff, murdering twelve people. Yet, the debate continues, while the toll of horrific acts perpetrated by ISIS and Islamic fundamentalism increases daily.

French President François Hollande declared immediately after the attack that the latter had targeted “the expression of freedom” that is the “spirit of the republic.” The connection with 9/11 was ubiquitous: the perpetrators “had to be” Islamic extremists.

We don’t know much about the gunmen in Tunisia, except for the names of the two who were killed during the raid, Yassine Laabidi and Hatem Khachnaoui: Tunisian officials claimed that they have not yet found evidence tying either of them to any known terrorist group. On the other hand, we have learned a lot about the Kouachi brothers since their attack. They were, indeed, Islamic extremists. Newspapers around the globe lingered on the troubled youth of these Algerian immigrants’ orphans. Chérif Kouachi had already been arrested at age 22 in January 2005, when he was about to leave France for Syria—a gateway for jihadists wishing to fight U.S. troops in Iraq.

Chérif was convicted a second time in 2008 (but sentenced to time served), for having assisted in sending fighters to militant Islamist Abu Musab al-Zarqawi’s group in Iraq, and for being part of a group that solicited young French Muslims to fight with Zarqawi.

After the first arrest, he had landed in the Fleury-Mérogis prison, where he met a convicted robber, Amedy Coulibaly. The latter appears to have coordinated his own terrorist attack with the Kouachi brothers, killing an unarmed French policewoman on January 8th and staging a siege inside a kosher supermarket the day after, where he murdered four more people.

One wonders, however, the extent to which Islam is to blame for the attack on Charlie Hebdo. It is true that the magazine had already been firebombed in 2011 after a cover depicted Muhammad saying “100 lashes of the whip if you’re not dying of laughter” (100 coups de fouet, si vous n’êtes pas morts de rire). It is also true that witnesses described hearing the attackers shout “Allahu akbar” and “We have avenged the prophet.” Furthermore, Nasr al-Ansi, a top commander of al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula, appeared in an 11-minute video claiming responsibility for the massacre. But to what extent was al-Qaeda really involved, and how much of this was an autonomous initiative of the Kouachi brothers? How much of the latter’s fanaticism was a consequence of their poverty, and of the inner problems of the French immigration policy?

The attack on Charlie Hebdo received widespread media attention. It totally obfuscated what happened at the same time in Nigeria, where Boko Haram, an Islamist terrorist group, used a 10-year-old girl as a suicide bomber in a market.

Why was there such overwhelming global support in France, and no widespread solidarity for the slaughter in Nigeria? We are still terribly Western-centric. And in our Western-Centrism, we equate Islam with fanaticism. I agree with Nicholas Kristof, who wrote in The New York Times on January 7th, that terrorists make very effective headlines, “but they aren’t representative of a complex and diverse religion of 1.6 billion adherents.” The obsessive mediatic coverage of the attack on Charlie Hebdo conveyed the narrative of an exclusively extremist Islam: it created a wave of terror and produced intolerance between communities and neighborhoods in Paris that had previously coexisted peacefully.

While it is impossible to undermine the tragedy of what happened in Paris, and it is fundamental to restate the importance of freedom of speech, it is also important to acknowledge that the vast majority of Muslims are not terrorists. They are themselves victims of terrorism: terrorism clouds our judgment of Islam, and prevents us from trying to understand the latter in different terms than those of fanaticism.

Meanwhile, a different kind of extremism benefits from such “mediatic terrorism:” the one of far-right parties, especially the French National Front, under the leadership of Marine Le Pen. The party’s president since January 16th, 2011, Le Pen, seeks to abolish the law enabling the regularization of the illegal immigrants, and is a strong opponent of the Euro.

Marine Le Pen used the attacks to vindicate her approach to immigration, and is now increasingly seen as a serious presidential candidate in the 2017 elections. “I think we must eradicate the cancerous cell that Islamic fundamentalism represents or we run the risk that it will spread,” she told Inigo Gilmore on Channel 4 News a few days after the carnage. Yet, as Cathy Newman of Channel 4 News put it, “the racial and religious faultlines, which have rocked France and reverberated around the world will surely only widen if Marine Le Pen gets her way.”

More recently, we saw the victory of Benjamin Netanyahu’s rightwing Likud party in Israel. Netanyahu keeps changing position on Palestinian statehood, while Palestinian leaders and Hamas’s members harshly reacted to his re-election.

We are far from a tolerant world. Hunted by the specter of religious fanaticism, we advocate for freedom of expression, but between real and mediatic terrorism, lethal drones and intrusive surveillance, there is little space for freedom tout court.