The European Union is committed to international peace and security. How many times have you read or heard a similar statement? The 2012 Nobel Prize winner likes presenting itself as a leading actor in supporting democracy and peace worldwide. This is far from reality. Although Europe remained the most peaceful geographical region in the world according to this year’s Global Peace Index, if we consider EU countries taken as a whole, the EU is one of the biggest arms exporters in the world.

Military expenditure in Europe has fallen slightly recently, but it still accounts for one quarter of global military spending. Some of the largest defence companies are head-quartered here. Five EU countries rank in the top-ten arms exporters worldwide. Thanks to a lax EU arms export policy, arms produced in the EU emerge in wars and human rights abuses worldwide. Saudi Arabia is by far our most important client.

A flourishing bloody market for the Great Four

World’s arms industry doesn’t seem to be particularly hit by the overall negative economic outlook. According to Swedish independent research institute SIPRI, sales of arms and military services by the largest arms producing companies amounted to $402 billion in 2013 (last year for which data are available). Among the top-ten arms producing companies stand the French Thales Group, the British BAE Systems and the Italian Finmeccanica, considered to be the jewels of the European arms industry.

BAE Systems is the biggest arms manufacturer in the UK and Europe, and the second biggest in the world, with around 95% (€30 billion) of its sales are military. Thales Group stemmed from France’s partial privatisation of the industry sector and is deeply involved in the militarisation of the Mediterranean undertaken by Frontex, together with Finmeccanica, the second largest Italian company with a turnover of €14.6 billion. These three companies, plus Airbus Group (formerly known as EADS), the so-called big four of the European arms industry, are intensively lobbying to boost their arms and military equipment exports and take advantage of EU funds for the research and innovation programmes.

Free trade in arms in the internal market

Arms industry lobbyists have intensively worked for the creation of the European Defence Agency, which was established in 2004 with the aim to “sustain the European Security and Defence Policy as it stands now and develops in the future”. In other words, to preserve a strong manufacturing capacity for war equipment at EU level by supporting joint arms programs and joint research and development projects in EU countries.

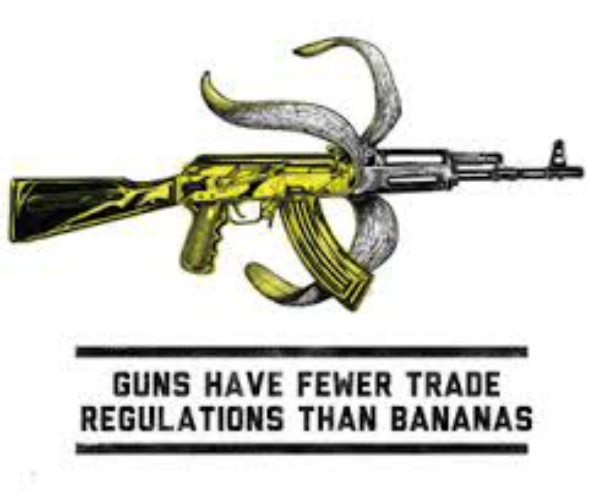

Thanks to extensive lobbying, EU arms dealers can easily export their weaponry worldwide. How ? One of the big successes of the arms industry was the introduction of a common system of licences for intra-EU sales of weapons. Since 2007, there are no internal weapons controls. So arms industries can trade within the EU market without having to apply for separate permits, and can use the EU country with the least stringent arms export legislation to export outside the EU. Even worse, many military products have a military-end use but do not need exports licences because of their ‘dual use‘ applications– that is, benign applications for arms.

EU arms export policy is “soft law”

In contrast to the liberalisation of the internal defense market, there is no legally enforceable legislation on arms exports. In 2008, a Common European Position on Arms Exports was approved by EU Member States according to which, eight criteria shall be taken into account before the issuing of arms export permits. For instance, EU countries have to consider “the existence of tensions or armed conflicts” in the country of final destination, or “the likelihood of armed conflict between the recipient and another country”. But these criteria are not legally binding, thus not enforceable before a court.

At war against an imaginary enemy

Scientific research is one of the largest expenditures for the EU’s budget: Horizon 2020 has nearly €80 billion of funding available over 7 years (2014 to 2020). Given the national budget constraints, one of the main goals of the arms lobby is to ensure that a consistent part of the funds intended for the research and innovation programmes goes directly to the merchants of war. The possibility to finance innovation in arms has been introduced by the Lisbon Treaty, whose provisions on security issues were written by arms industry lobbyists sitting in the European Convention’s defense working group. Israel is the most active non-EU participant in the Horizon programme: this means that its arms companies benefit vastly from the grants.

Security is one the research areas available for fund (with a package of €3.8 billion). Quite unsurprisingly, in our war-on-terror society one of the lines of applied research in security matters is “strengthen security through border management”. The securitisation of irregular migration paved the way for the militarisation of security borders, which is fundamental to the needs of the EU arms industry: migration becomes a problem that has to be resolved in the same way as crime, terrorism or drugs. With more ‘security’.