As one of the most widespread and important Avant-garde art movements in the early 20th century, cubism drew much of its inspiration from modern metropolitan lives at that time. Artists in Prague were largely affected by French cubists, in fact, the capital of today’s Czech Republic was the most active center where cubism thrived outside Paris. In the early 1900s, Czech art circle was eager to find a way to break away the established Viennese cultural artistic style, therefore adopted avant-garde, and look for inspirations from western Europe. Czech Cubism was first exhibited in 1912 by the Group of Fine Artists in the Municipal House. Having received the influence from German Expressionism, Czech cubism differed from French cubism in that the artists incorporated the expressive power of colors and tones into the fragmented forms, the art style was thus also known as cubo-expressionism, with Bohumil Kubišta being a leading figure.

It has always seemed unfair to me that Czech Cubism received much less attention than it deserved, mostly overshadowed by WWI and its subsequent socio-political changes that took place in continental Europe. True, Czech cubism was a short-lived art movement compared to others, from 1912-1914, its implications on modernity were nevertheless long-lasting, even until today.

Dynamism

Pablo Picasso, 1910, Girl with a Mandolin (Fanny Tellier), Oil on canvas, 100.3cm x 73.6 cm | Museum of Modern Art, New York, U.S.

Be it French or Czech Cubism, both challenged the established classical ideal by depicting multiple viewpoints with cubic fragments to create three-dimensionality on a flat canvas, the fragmentation, as a way to restore reality.

Georges Braque, September 1909, Violin and Palette (Violon et palette, Dans l’atelier), Oil on canvas, 91.7cm x 42.8 cm | Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, U.S.

While French Cubism was characterized by its almost “fauvistic” representation of overlapping and smashed cuboid forms, Czech Cubism was characterized by its cleanness, harmonious and regular arrangement. The same was also seen among its furniture, interior design and architecture.

Praha – Ovocný trh – Museum Kubismus / of Cubism – View Upwards on the Staircases | Wikimedia Commons

The prewar 20th century, was a dynamic, if not, dramatic time for the globe. Rapid industrialization and urbanization, immigration, further establishment of world economy and the rise of new world powers, Prague was no exception. Indeed, as the Czech nationalistic sentiment rose in the 19th century, the land has entered its modernity when it identified the need to establish a unique national identity. During the 20th century, Prague was also one of the most industrialized cities in Bohemia and Moravia.

Individualism

French and Czech cubists differed the most in their understanding of the reality. The former maintained a more commonsensical presupposition of the independent existence of the outer world, in which objects carried their own inner energy which could only be released by splitting the horizontal and vertical surfaces that restrain the conservative design, the intrinsic needs of the human soul were less valued by the artists. French Cubism could usually be characterized into two main stages, namely, analytical and synthetic cubism respectively. The former aimed at constructing the true reality, by breaking the restriction of 2-dimensional canvas, an object/ subject can be seen in a 3-dimensional perspective, whereas the latter was characterized by the flatness, restoration of the use of color from the subdued and monochrome palette found among Analytical Cubism, they looked more like collages than oil paintings.

On the other hand, given that some advocates of Czech Cubism were close to German expressionists, such as Bohumil Kubišta who was also a member of Die Brücke, Czech cubists combined the three-dimensionality with the expressive use of color.

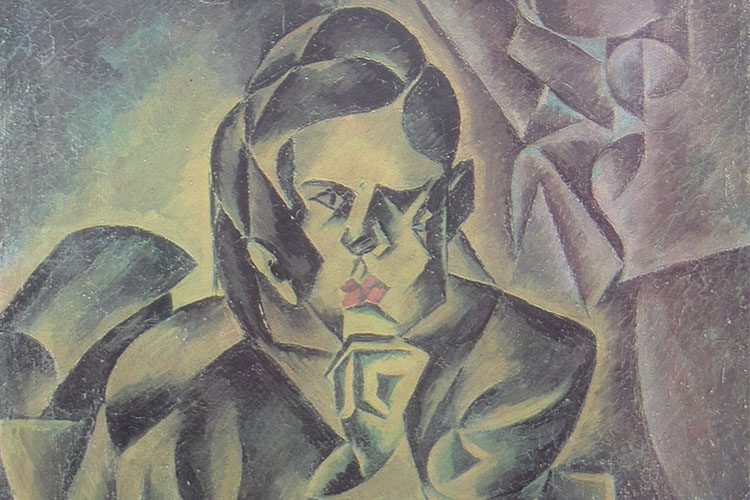

Bohumil Kubišta, Self portrait, 1908, Oil on canvas, 91cm x 65cm | Regional Gallery of Fine Arts, Zlín, Czech Republic

One of the deepest problems of modern life is, according to Georg Simmel, “the attempt of the individual to maintain the independence and individuality of his existence against the sovereign powers of society.” The German sociologist believed that the dynamic metropolis reinforced the dependence of man on differences to discover one’s reason for existence as an individual. It is thus an irony that man’s intellectualistic quality created the metropolis that we are now so desperate to escape from, using the same quality as a shield! Consider the money economy that many are against these days, it actually rose to prominence because of our intellectual need to reduce our mundane lives into mathematical terms in the first place.

Isolation

One many wonder the relationship between beauty and geometry. True, why has this been the attention of artists since the Renaissance? As mentioned in my previous article on artistic development and evolution, art and science were never separable from each other. Recently, scientists also start to explain aesthetic with neurology, an exhibition named “Beauty and the Brain Revealed” took place AAAS Art Gallery in Washington, D.C. to discover audiences’ brain activity when viewing different artworks, to discover what a scientific account for beauty. Neuroscientist Semir Zeki suggested that mathematical beauty and visual, musical and moral beauty stimulate the same part of the brain. In the context of philosophy, Kant also argued that pleasure that we derive from mathematical equation is that it makes sense, to either logical/ deductive/ inductive system of the brain. For centuries, the Czech education had been focusing on mathematics and geometry, it is no wonder that Cubism found the firm soil in the Czech land.

To Kubišta, one powerful strength of art lies exactly in that it brings salvation to our miserable modern lives. In his essay titled “Towards the Spiritual Essence of the Modern Age,” the artist declared that “…what we demand of new art, and what can bring us the ultimate satisfaction, is a transformation of its inner intellectual essence.” The artist’s 1912 painting St. Sebastian provides a great illustration to his view on the role of art.

Bohumil Kubišta, St Sebastian, 1912, Oil on canvas, 98cm x 74,5cm, The National Gallery in Prague, Prague, Czech Republic

Stylistically, the artist incorporated what he called “transcendental forms” in this defining painting to his career, which meant the fundamental geometric shapes, surface, lines, as well as the interrelation between the latter two. In terms of symbolic meaning, Kubišta’s version of St. Sebastian was unlike any other depiction with rich religiosity since Renaissance.

Andrea Mantegna, Martyrdom of Saint Sebastian, c. 1480, Tempera on canvas, 255cm x 140cm | Louvre Museum, Paris, France

Rather, the artist related his own fate in struggling against the public and art critics’ understanding of his work. The symbolic meaning of life and death was heightened by the subdued, brownish-monochrome color palette.

Peter Paul Rubens, The Martyrdom of Saint Sebastian, c. 1608, Oil on canvas, 153cm x 118cm | Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Antica di Palazzo Corsini, Rome

As our world evolved from mechanical to organic solidarity, as coined by the Jewish sociologist Emile Durkheim, isolation is no longer the negative state of solipsism, but one essential ritual that takes place inside our own minds to abstract from the mundane lives.

The only way to give into the external reality is thus through withdrawal, only then could we establish our own selves without getting lost.