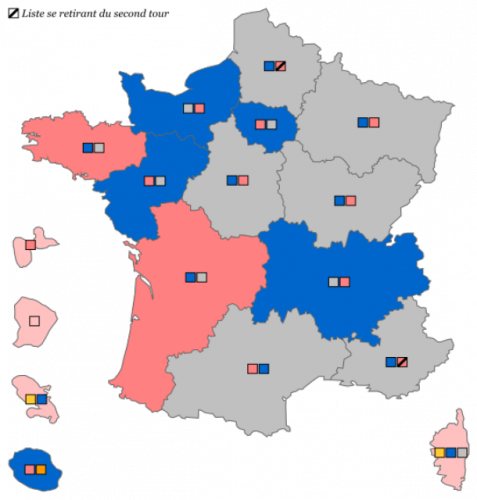

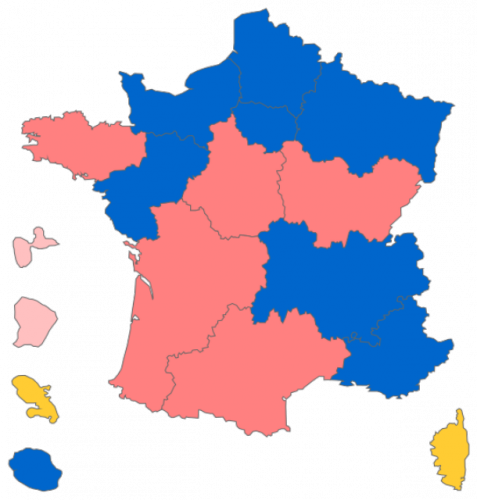

France’s far-right party, the Front National (FN), was ahead in 6 out of 13 regions in the first round of regional election voting on December 6th – and yet, failed to win a single seat after the second round. This did not occur due to a massive loss of support. The FN suffered at the hands of a Socialist-Republican collaboration; Hollande’s Socialists urged supporters in certain areas to vote for Sarkozy’s centre-right, so keeping Le Pen’s nationalists out of power.

Yet, the FN garnered a total of 6.8 million votes – by far their largest ever. This record-breaking support is a threat to establishment parties; “tonight, there is no place for relief or triumphalism or message of victory [against the FN]”, declared Socialist Prime Minister Manuel Valls.

Rising Front National Support

Why is the increased support for the Front National significant and what does it mean for other parties? The “risk” associated with its hypothetical rise to power derives from its reputation as neo-fascist and xenophobic. With tensions surrounding immigration and terrorism at their apex, Marine Le Pen’s controversial comments – such as that comparing Muslim immigration to Nazi occupation – are difficult to ignore.

For some, this attitude is one of the main draws of the FN – and the climate of fear in France following the Paris attacks has certainly helped. In fact, an exit poll reports 16% of FN voters changed their voting intentions after November 13th. But surely the election’s timing cannot account for the party’s recent avalanche of support.

Despite the FN’s racist image being toned down since Jean-Marie Le Pen’s expulsion in 2011, it has maintained other representative qualities: uncompromising attitudes toward immigration, anti-establishment socioeconomic policies, and separatism from the E.U.

France faces unemployment over 10% and some of the highest taxes in Europe; Le Pen’s party has effectively capitalised on poor conditions and security fears. The FN’s disproportional popularity amongst those without academic backgrounds is no coincidence: the unemployment rate across the country is three times higher for those without a high school diploma.

Larger Political Influence

The Socialist and Republican parties describe the FN as dangerous due to its fascist rhetoric – however, it is not hard to imagine their main concern being the party’s anti-establishment attitude, threatening their longstanding positions as France’s mainstream parties.

This fear explains the Socialist willingness to sacrifice voters to prevent an FN victory, as well as the toughening in Republican attitudes toward the refugee crisis and terrorism. Both establishment parties are making concessions toward the right for the sake of their own power. Much like the U.K. Independence Party, the FN has shifted its country’s whole political scene.

But despite the 6.8 million votes, despite the influence on other parties, it is important to remember the Front National did not win a single seat in the elections. Pascal Perrineau, politics analyst at the CEVIPOF institute in Paris, stated:

The National Front is still struggling in the second round, and it’s struggling to become a mainstream party, a winning party.

This may be an exaggeration: the FN was the national leader in the first round, and its ultimate loss was largely caused by Republican-Socialist tactical voting. But the truth remains that, if so many sacrificed their left-leaning ideals just to prevent an FN victory, it remains a fringe party. According to Emile Chabal of The Hindu, “its value is principally as a party of protest, not a party of government”.

Such “parties of protest” typically perform better regionally than nationally; this causes some to consider an FN victory in the 2017 presidential elections an impossibility. Even with the wave of separatist nationalism sweeping over Europe, parties of the far-right have been unable to obtain over 30% of the vote and only entered government through coalitions.

That is not to say the Front National should be underestimated. Its influence is at a record high and unlikely to decline in the near future. But the “threat” of the FN could be a positive in France’s political scene, acting as a warning to other mainstream parties and forcing them to address issues such as high unemployment and rising inequality. The FN’s popularity reflects widespread concerns over austerity policies and globalising economies, leaving governments unable to implement their own reforms.

What the FN considers a “popular uprising against the elite”, a reaction against inefficient establishment parties, should take the form of an inclusive, socially-conscious call for reform. Rather than blaming economic troubles and unfair austerity measures on immigration, citizens should consider what brings them all together to fight major issues like climate change and corruption. This would prove less socially divisive and less dangerous – although the FN does not believe in aggressive foreign policies partly responsible for crises in the Middle East, its ultra-nationalist views are more likely to drive oppressed communities toward extremism.

Daily Beast journalist Christopher Dickey claims the Front National has “become not just a third party in the multi-party French system, it has become the third party”. Perhaps it is time for a fourth party to enter the scene, a collective of citizens concerned over the FN’s divisive rhetoric but equally unsatisfied with the status quo as its far-right supporters. Only then can France hope for effective reform without plunging into Islamophobic and short-sighted hysteria.