What happens if you try to join multiple traditions and abolish cultural differences?

Nepal recent events often captured the media attention due to the violence with which opposers to the new constitution expressed themselves, but which are the reasons that led to such an aggressive reaction?

Nepal first constitution was enacted in 1950. Sixty-five years and six constitutions later, Nepal promulged its new constitution raising very significant disapproval in the public opinion. For the first time in the country’s history, a Constitution not written by the monarchs, but written by elected people in the Constituent Assembly (CA).

The Constituent Assembly main purpose was trying to bridge and overcome the social and ethnic divisions existing in the country and create a political structure where different ethnic and social groups – especially the excluded ones – would be part of a more inclusive order and exercise power. Unfortunately, based on South Nepal attitude towards this new constitution, seems like the CA objectives are still far from obtained. Constituent Assembly could have meant an historic opportunity for Nepal, but something went wrong when in 2013, an Assembly dominated by the traditional parties gained once again the power. The process through which the Constitution has been adopted appears questionable and probably hijacked by a few leaders, all belonging to the upper caste communities.

Socially marginalized groups, like the Madhesis, who live mostly in the Terai area, Janajatis (indigenous people), and women, have strong objection to the provisions of the constitution and felt particularly left out of this new process which was indeed supposed to give them a voice in the crowd.

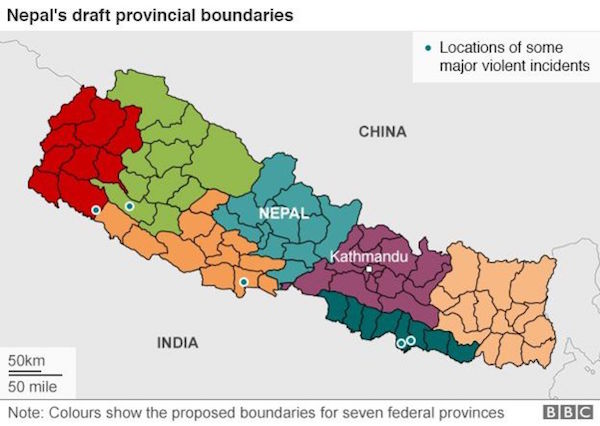

The new document drew up new boundaries for seven new-born states. Compared to the previous constitution the new document expects that a smaller percentage of parliament will now be elected by proportional representation – 45%, instead of 58% in the previous post-war interim constitution.

Nepalese women appeared very concerned about the new constitution, which is, in their opinion, discriminative in a society already much more than patriarchal. According to the new constitution, in fact, it will be difficult for a single mother to pass her citizenship to her child and if a Nepali woman marries a foreign man, their children won’t become Nepali unless the man first takes Nepali citizenship. Vice versa, if the father is Nepali, his children can be Nepali regardless of the wife’s nationality.

The Madhesi community, in eastern Terai, socially close to their indian neighbors, complain that the above citizenship measures will disproportionately affect them because of their many cross-border marriages. On the conservative side of the population instead, unhappiness is due to the awareness that Hindu groups have that the restoration of the country’s officially Hindu status – abolished nine years ago – is becoming an always further hypothesis.