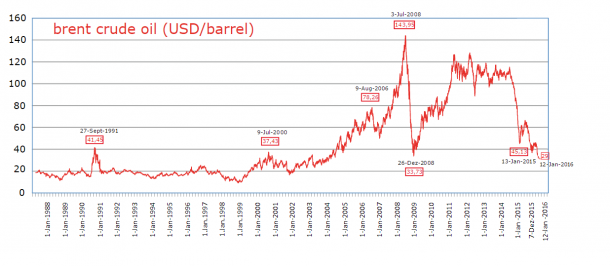

As of January 2016, oil prices continue dropping. The International Energy Agency (IEA), an intergovernmental organization established in the wake of the 1973 oil crisis, reported that it has dipped below $30 a barrel (around 28-29 dollars depending on the benchmark) on January 12th; the trend is not likely to halt in the foreseeable future. But which are the reasons behind the drop, and what does it imply for the economy?

To put it simple, the main reason is persistent oversupply.

In the last years, technology has improved enough to allow extractions which had not been possible in the past; the main example is the extraction from shale formations using hydraulic fracturing (shale gas). This had impressive effects on global balances. Through shale gas extractions, U.S. domestic production has nearly doubled over the last years, diverting oil imports from countries such as Saudi Arabia, Nigeria and Algeria which needed to compete in different markets, forcing price reduction.

But production has not increased only in the United States. It kept rising also in the Gulf of Mexico, in Canada from tar sands, in Iraq, and it is likely to boost in Iran after the recent nuclear deal.

How does the drop in oil prices affect economies and countries worldwide?

People may assume that motorists, many firms, lower and middle-income groups are likely to benefit from the price drop, due to the fall in the price of diesel, heating oil and natural gas prices. In the short run, this is the case. The persistence of the drop, however, is soon likely to generate different effects.

As it may be easily understood, the drop implies lower earnings for oil companies, and, therefore, thousands of employers. Chevron, Royal Dutch Shell, BP, to name just a few, have all announced job cuts and slashed planned investments between November and January. The New York Times reported that an estimated 250,000 oil industry jobs have been lost worldwide since the long price decline began.

Oil-producing countries are affected as well, suffering economic or even political turbulence.

According to BBC, Russia loses about $2 billion in revenue for every dollar fall in the oil price, and as Prime Minister Dmitrij Medvedev explained in 2015, the twin impact of falling oil prices and sanctions led the country to cut spending and devaluate. Yet a devaluated rouble means that Russians are going to buy much less worldwide, therefore affecting the economies of export-oriented countries which have strong connections with them. But it is not only Russia’s case. Brazil, Ecuador, Nigeria, Venezuela are also “petrostates”.

Even Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Qatar, and the other Persian Gulf States, in spite of their huge reserve funds, are likely to invest less money around the world and cut aid to countries like Egypt, in order to adjust to the dropping revenues.

Analysts believe that production will probably decrease and price rise sometime between the late 2016 and the early 2017; in the main time, oil price reduction is likely to disadvantage oil producers and somewhat benefit consumers, opening a window of opportunity for the making of investments and better policies in a few, lucky countries.