It’s no surprise that, as the world’s economy becomes more competitive and globalised and finding a job grows increasingly difficult, college students lean towards STEM (science, technology, engineering, and math) subjects. With the high cost of college education, often involving taking out student loans, students choose their major based on their employment prospects after graduation. According to a 2014 U.S. Department of Education report, the average salary of a STEM major is $65,000, as opposed to the $49,000 average for non-STEM majors. The difference is even more striking when you look at the average salary of humanities students (including history majors), $43,100, in contrast with that of engineering specialists at $73,700. As Virginia Postrel explains in a Bloomberg View column:

It’s simply not the case that students are blissfully ignoring the job market in choosing majors. Contrary to what critics imagine, most Americans in fact go to college for what they believe to be “skill-based education”.

The economic pressures on millennials, especially young graduates, are unprecedented – the fact that they aim for “employable” degrees is understandable. Even within the humanities & social sciences, degrees like economics and international relations are valued more than a degree in their sister area, history. Politicians, diplomats, CEOs and NGO directors, while often not having received a STEM-based education, are rarely history majors. Perhaps the current landscape of non-STEM fields, dominated by economics majors and lawyers, is why many students shy away from their interest in the study of the past.

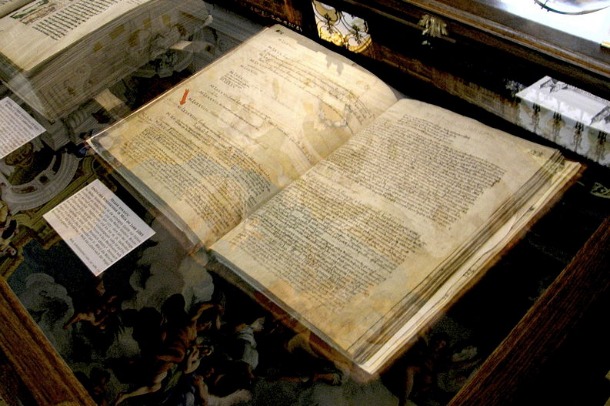

And yet, there are countless benefits to studying history – whether as a college major, a co-curricular interest, or at least as a high school subject. The foundation of history is not based on, as many imagine it to be, random facts about English kings or dates of battles. It is perhaps the subject that best helps us understand the world we live in, drawing from several disciplines and examining them in different cultural contexts. It tells us not only about human nature and past mistakes, but also of our current society by taking into accounts trends in historiography (the study of historical writing, methodology, and interpretation itself). It can help us make decisions essential to the functioning of our social world.

You cannot hope to understand people and societies without having studied history. Thus, any discipline reliant on data about people’s behaviour is also reliant on history to draw conclusions. This applies to a vast number of fields: from business & economics to war studies, from government to social psychology & sociology… Many social sciences are turning towards a more numerical, scientific approach in understanding the operations of people. While this is certainly essential in data collection, humanity is too complex to ever be represented by simple numbers. Take a psychologist, for example, investigating stress levels and coping mechanisms in millennials as opposed to older generations. Their research, collected through interviews and questionnaires, can be generalised and converted into numerical data. But once it is established that millennials do indeed suffer from more stress & anxiety than their ancestors, only history can explain why that is. Only history can illuminate us on shifts in economic policy and social expectations through the decades, causing this unprecedented rise in mental health issues.

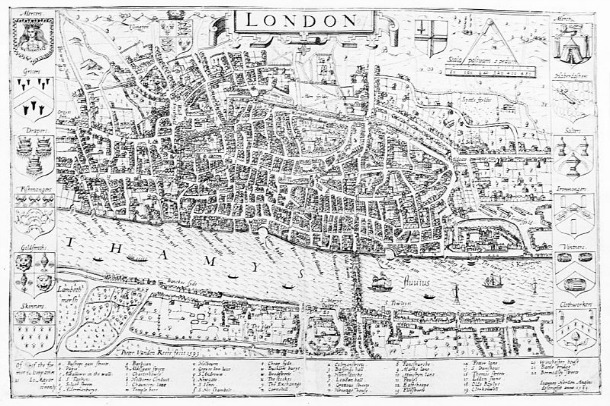

Only history can give an account of the deep-rooted differences between Western and Eastern societies of today, while also shedding a light on their similarities. Only history can tell us why anti-establishment political sentiments have reached an apex in the United States, or how the Islamic State has grown so powerful in the Middle East – an area where trade and culture once thrived. Without knowledge on the Transatlantic slave trade, on the unsung heroes of the feminist & civil rights movements – and why they remain unsung – you cannot understand the aims, the intricacies of the current Black Lives Matter movement. Tracing back Chinese anti-foreign sentiments to unprofitable trade deals under the Qing dynasty, you can better examine Chinese communism. Any understanding of social justice and policy-making, of societal trends and humanitarian aid, remains shallow without a broad historical base to underpin it.

As Peter N. Stearns of the American Historical Association summarised:

The past causes the present, and so the future. Only through studying history can we grasp how things change; only through history can we begin to comprehend the factors that cause change; and only through history can we understand what elements of an institution or a society persist despite change.

As for career prospects shifting away from the humanities – while there currently is a higher value placed on STEM fields, this is likely to change in the near future. According to Cathy N. Davidson of the MacArthur Foundation, 65% of today’s children will hold jobs that have yet to be created as the jobs of today become obsolete. Younger generations will have the freedom to shape the economy in a novel way, redistributing values across disciplines – and in fact, erasing the artificial lines differentiating between one discipline and the other. This will make industry as a whole more creative, more open, and more interdisciplinary. Understanding how people work and applying scenarios to real-world settings – two skills honed by the study of history – will be particularly sought-after.

But even today, the skills a history degree can help you develop are employable and transferable across fields. The ability to examine conflicting interpretations, to collect evidence, to identify and understand change in society, to write eloquently in support of your argument while remaining aware of its limitations… It is hard to imagine all this leaving you unable to find a job. This is particularly true when a history degree is coupled with advanced studies in related fields such as law, journalism, or politics. The public sector also heavily relies on history: both as a discipline providing the bulk of data for social research, and through owners of history degrees who work as civil servants, curators, diplomats and more. Not to forget is the direct career path to research and academia, essential in educating the doers of tomorrow. And of course, if you are as successful in this field as Ron Chernow has been, your biographies may even inspire a Grammy-award winning musical.

One of the most exciting proposals for history’s place in today’s world is “The History Manifesto”, by Jo Guldi and David Armitage. It is “a call to arms to historians and everyone interested in the role of history in contemporary society”; its authors argue for a shift to long-term narratives over shortsighted ones, and for a wider place for history in the digital age. They highlight how, in the mid-1900’s, historians had a significant influence on policymakers, international development, and NGOs among other institutions. But the hope is that in the near future – as interest in history grows and even becomes more necessary – historians will not simply be behind-the-scenes advisors. They themselves will be leading governments and development agencies and making important decisions with the broad perspective one can only gain from a history degree.

What you should be aiming for in college is knowledge on how to be a better citizen, how to understand and find a place in our society – not only how to fill in a resumé. The key word we hear in reference to today’s world is “change”; rapid change in global markets and international developments, change in our societal landscape, change in how we live our lives as compared to even a couple decades ago. History, by default the study of human development across time, is what can best equip us to deal with these changes – as well as take an active role in directing them in the right direction.

Connect with us on social media via Twitter, Facebook and Instagram.Your opinion matters!