[translations idioma=”ES” url=”https://archives.rgnn.org/2013/10/09/chile-entre-elecciones-presidenciales-y-lecciones-del-pasado”]

CHILE. Last week, Chile’s incumbent President Sebastián Piñera gave a speech in front of the UN General Assembly to congratulate the sustained economic growth of his country. According to the President, the nation’s prosperity stems from its successful transition to democracy post-1990, when dictator Augusto Pinochet was forced to abandon La Moneda after losing a national referendum. However, the President’s positive outlook is not shared by most Chileans, and only radical structural changes can address the socioeconomic challenges it faces this upcoming decade.

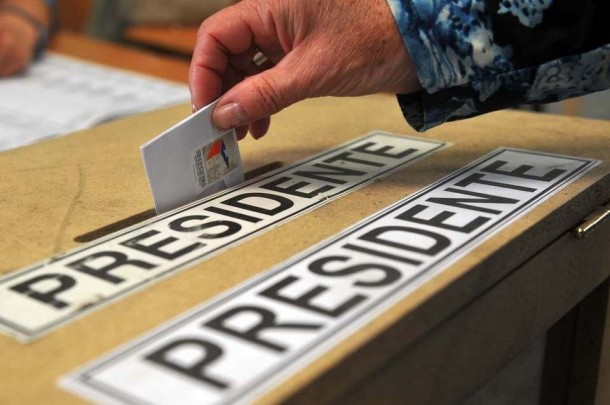

The responsibility will fall on the winner of the Presidential elections that will be held on November 17, 2013. One issue demands immediate attention: Augusto Pinochet’s legacy. According to a recent survey by the Centro de Estudios de la Realidad Contemporánea, 75% of Chileans believe that the dictator’s influences still remain despite more than 20 years of democratic governance.

Thus it is not surprising that Michelle Bachelet, former President and the main candidate of the left, is the favorite to win the election with a rating of 44%. Evelyn Matthei, the right’s candidate, only enjoys a mere 12% of support. Mathttei is the daughter of one of the generals that remained faithful to Pinochet until the end, Fernando Matthei. Though many sectors of the civil society have apologized for their indirect support to the dictator, Evelynn Matthei has publicly stated that she will not apologize since she was “only” twenty years old when the coup took place.

Bachelet has already taken up the mandate of the people and has promised to reform the Constitution. The Magna Carta was ratified by Pinochet in 1980 and subsequently reformed before he stepped down from power in order to preserve certain institutional legacies, limit basic rights and circumscribe political opposition. The limits and rigidities were built in to guarantee that the neoliberal policies Augusto Pinochet employed from the outset of his military dictatorship would be continued. Though Chileans have mostly elected leftist presidents since 1990 (Piñera was the first Conservative to reach power since the end of the dictatorship), Pinochet can still smile. None of them, including Bachelet, made any significant steps to modify Chile’s economic policies and correct the blatant inequalities with which its citizen live.

Chile can proudly state that it has consistently been growing at a rate of more than 6% – one of the fastest developing countries in Latin America. But, according to the OECD, among the Latin American countries, Chile also has the highest level of income inequality stemming from severe structural problems.

One of these structural problems is Chile’s education system. There is no free public higher education system, and the State only devotes 0.4% of its GDP to education, according to the 2011 November/December NACLA report by J. Patrice McSherry and Raúl Molina Mejía. This rate must drastically increase if Chile aspires to “produce” (if this word can be used when talking about people) its own talent and future leaders. Poor and middle-class students are burdened with debt since the fees charged by the universities are higher than the national minimum wage, which amounts only to $363 a month. Due to financial problems, 80% of university students never earn a degree.

This terrible situation has been spurring ongoing protests since 2006; last April alone saw more than 150,000 students marching in Santiago, the nation’s capital, to demand education reforms. On top of the student protests, several general strikes have been initiated by workers affiliated with the CUT (United Federation of Workers), the main union of the country. With ever increasing strength, the workers, in addition to supporting the students, have been demanding a new labor code, public pension system, and the renationalization of vital natural resources such as copper, privatized by Augusto Pinochet.

Pinochet’s main legacy was not simply the Constitution he forced onto a democratic Chile, but rather, the unfair economic policies and inequality contained within. These neoliberal policies need to be abandoned or Chile’s further social and economic development will be thwarted by increasing social unrest and exponentially growing inequality. No ascending nation, and even less one that aspires to become one of the richest nations, should permit this.

The OECD, in its 2012 report, already provided deep analysis and a paramount suggestion for Chile to follow: the country’s poverty and inequality remain wide because the tax-benefit system currently in place does very little to redistribute income, what explains why the economic growth that Chile has experienced the last 20 years has not translated into a more important reduction of inequality. Chile’s challenge is to increase its inter-generational mobility (for which a good public education system is mandatory) and maintain its high growth while distributing the gains more fairly across society.

All political parties and candidates, especially Michelle Bachelet, should recognize the challenge they face and go to the polls conscious of the responsibility that may fall on them in November: a historical possibility to influence the future of their country, but what will undoubtedly be a heavy burden.