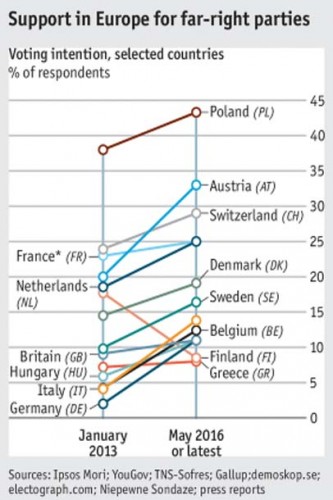

Before this decade, you may have been forgiven for thinking that the far-right ideologies that had torn Europe apart for half a century could only be found in history books. Nationalism (defined by strong patriotism, often with a sense of superiority over other countries) and Fascism (extreme right-wing patriotism, implemented to terrifying results by Mussolini and Hitler) showed empirically they had nothing to offer but division, fear and ultimately war. And yet, in 2016 a resurgent far-right across Europe proves even the worst ideas can’t be killed off forever.

The rise of far-right, the economic & refugee crisis, the precariousness of the EU; none of these changes is good news for the EU, which has suffered a huge blow recently as a result of the Brexit vote. There is not doubt Germany, France and other nations have been hardened in their worldview and openness to immigration by both economic & refugee crises. Nevertheless, if Europe is to survive and thrive again, it cannot forget its history and wander down the dark path the far-right has led it down too many times already.

On the Right

By The Economist

In Germany, the right wing populist party, Alternative for Germany (AfD) has never been more popular than it is now. Off the back of anti-refugee sentiment fuelled and pushed by far-right, anti-Islam movement Pegida, Germany has veered to the right in recent times. As broadcaster and journalist Paul Mason of the Guardian says;

“The combined rise of authoritarian nationalism, outright fascism and anti-minority racism in the east of Europe should alarm us.”

The attacks that took place on New Year’s Eve in Cologne in which up to a 1,000 women were reportedly attacked, Angela Merkel’s humanitarian gesture of allowing in over a million migrants and asylum seekers have only heightened tensions between those hostile to the biggest migration of people since the second World War and those more sympathetically inclined. Similar rises in the far-right can also be found in France (the National Front), Austria (Freedom Party of Austria) Hungary (Jobbik) and Greece (Golden Dawn).

On the Left

In contrast, Southern Europe has seen a rise of left-wing parties, notably Podemos in Spain and Syriza in Greece. Both parties have emerged from nowhere in the last few years, taking the political establishments of both countries by surprise; Podemos came 3rd in the Spanish national elections in June 2016, having only been in existence for just over two years.

Global Citizens

Global Citizenship can be defined as;

“For some, it might be about the projection of economic clout across the world. To others, it might mean an altruistic impulse to tackle the world’s problems in a spirit of togetherness – whether that is climate change or inequality in the developing world. Global citizenship might also be about ease of communication in an interconnected age and being able to have a voice on social media.”

By GlobeScan

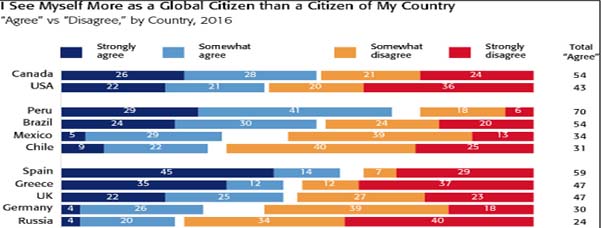

These political changes are occurring alongside those that beginning to see themselves more or less as global citizens. Spain, in particular, has correlated with a poll carried out by GlobeScan. Taken in 18 different countries, it asked people if they identified themselves as primarily global citizens, as opposed to national citizens. As the image above shows, the results correlate; Spain and Greece are both ahead in terms of Global Citizenship. Germany’s shift over the years is particularly notable;

“This (latter) trend has been particularly pronounced in Germany where the poll suggests identification with global citizenship has dropped 13 points since 2009 to only 30 per cent today (the lowest since 2001).”

Patterns Emerge

copyright: GlobeScan

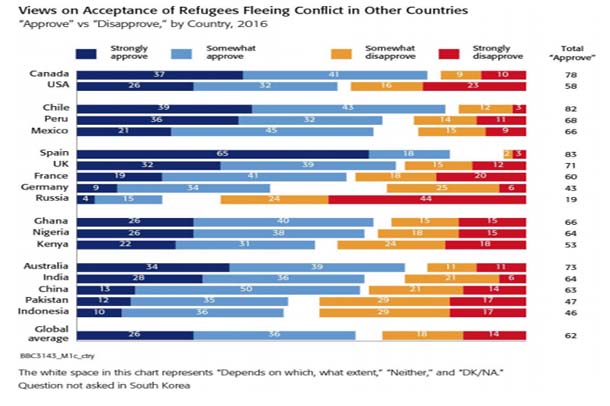

There are some obvious patterns here; namely, countries in which refugees settle and countries which suffered the most due to the financial crisis. Greece and Spain were both hit hard by austerity imposed up them following the financial crisis in 2008 and are still suffering as a result, leading its citizens to protest in huge numbers. Of the two, only Greece has experienced the kind of migration Western European nations have such as France and Germany, and even though has seen its fair share, it is usually only a transit state for the current wave of migrants and refugees (usually only staying because they’re forced to), as they seek homes in wealthier nations. The political fallout is therefore not as severe. Spain, in contrast, has only taken in 305 refugees compared to Germany’s 1.1 million.

Turning to the economic crisis, Germany fared the best, even being relied on bail out the sinking Southern European ships. And in terms of immigration, it has been Germany (as well as France, Sweden, and Austria) that has all taken in a huge number of refugees.